Unit 20 Economics of the environment

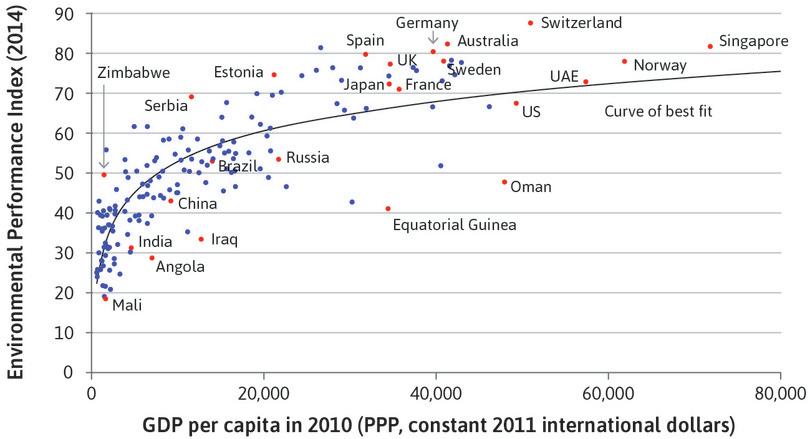

How economic activity affects the fragile biosphere of our planet, and how the resulting environmental problems can be addressed

- Production and distribution of goods and services unavoidably alter the biosphere.

- Climate change resulting from economic activity is a major threat to future human wellbeing, and it illustrates many of the challenges of designing and implementing appropriate environmental policies.

- Well-designed environmental policies implement the least-cost ways of reducing environmental damages and balance the cost of reducing environmental damage against the benefits.

- Some policies use taxes or subsidies to alter prices so that people internalize the external environmental effects of their production and consumption decisions; other policies directly prohibit or limit the use of environmentally damaging materials and practices.

- Some environmental systems exhibit processes of degradation, in which substantial and hard to reverse environmental damage occurs abruptly. Prudent policies avoid triggering such processes.

- Evaluating environmental policies raises challenging questions about how to value our natural surroundings and the wellbeing of future generations.

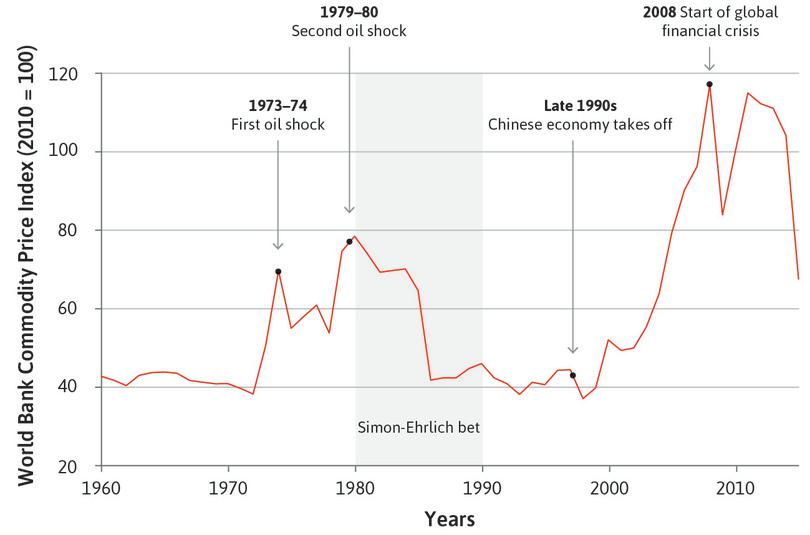

In 1980, one of the most famous bets in science history took place. Paul Ehrlich, a biologist, predicted that rapidly increasing population would make mineral resources scarcer. Julian Simon, an economist, thought that humanity would never run out of minerals because higher prices would stimulate the search for new reserves, and ways of economizing on the use of resources. Ehrlich bet Simon that the price of a basket of five commodities—copper, chromium, nickel, tin, and tungsten—would increase in real terms over the decade, reflecting increased scarcity.

- inflation-adjusted price

- Price that takes into account the change in the overall price level.

On 29 September 1980, they bought $200 of each of the five commodities (a total wager of $1,000). If prices of these resources went up faster than inflation over the next 10 years, Simon would pay Ehrlich the difference between the inflation-adjusted prices and $1,000. If real prices fell, Ehrlich would pay Simon the difference. During that time, the global population increased by 846 million (19%). Also during that time, income per person increased by $753 (15%, adjusted for inflation in 2005 dollars). Yet, in those 10 years, the inflation-adjusted prices of the commodities fell from $1,000 to $423.93. Ehrlich lost the bet and sent Simon a cheque for $576.07.

The Ehrlich-Simon bet was motivated by the question of whether the world was ‘running out’ of natural resources, but an interval of 10 years is unlikely to tell us much about the long-run scarcity of raw materials. The basic framework of supply and demand (see Units 8 and 11) tells us why. Commodities such as copper or chromium generally have inelastic (steep) short-run demand and supply curves because there are few substitutes for these resources. This means that relatively small demand or supply shocks generate large and sudden changes in the market-clearing price, similar to the market for crude oil that you encountered in Unit 11.

The World Bank. 2015. ‘Commodity Price Data.’

But what should happen to the price and availability of copper or chromium in the long run?

As the price of copper rises, producers have an incentive to invest in new technologies that will make its extraction cheaper. Consumers will substitute away from copper to other raw materials. Both of these forces push prices down.

As prices of copper begin to fall, firms cut down on new extraction investments and consumers demand more copper. This pushes the prices back up. The presence of market prices for raw materials therefore ensures that despite increases in population and affluence, we do not ‘run out of resources’. The ratio of known reserves to production does not fall far.

- resources (natural)

- The estimated total amount of a substance in the earth’s crust. See also: reserves (natural resource).

Over the last 200 years, prices for many mineral resources have not changed much, although extraction has increased dramatically. Although prices fluctuate from year to year, the overall trend is flat. This indicates that the supply of many raw materials in the earth’s crust—natural resources—is quite vast.

The transformation of living standards since the Industrial Revolution has been possible because of the combination of human ingenuity and available resources in the form of air, water, soil, metals, hydrocarbons like coal and oil, fish stocks, and so on. These were all once abundant and free, apart from the costs of extraction. Some, like hydrocarbons and mineral resources, are still abundant. Others, like unpolluted air, biodiversity (including coral reefs and many land and marine species), forests (due to deforestation and desertification), and clean water, are becoming scarce.

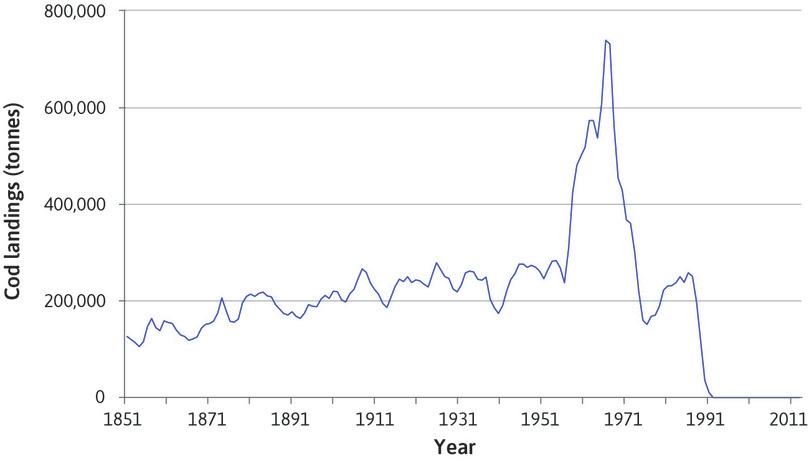

But the absence of prices is not the only reason why managing renewable natural resources is so hard. In some cases, the fragility of our environment under pressure from the growth of economic activity can lead not only to progressive degradation, but also to accelerating, self-reinforcing collapse. An example is the Grand Banks cod fishery, in the north of the Atlantic Ocean. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, legendary schooners such as the Bluenose (Figure 20.2) raced back to port to sell their catch to be the first on the market, and to offer fresh fish. By the late twentieth century, the Grand Banks had sustained the livelihoods of the US and Canadian fishing communities for 300 years.

Then suddenly, the fishing industry in the Grand Banks died and, along with it, many of the old fishing towns. Figure 20.3 gives the quantity of cod caught over 163 years, showing a gradual upward trend and a pronounced spike coinciding with the introduction of industrial fishing less than 50 years before the eventual disappearance of cod from the Grand Banks. You learned some reasons why an open-access resource is likely to be overexploited in Units 4 Unit 12, and it appears that in this case the cod was greatly overfished. North Atlantic fisheries are now recovering after governments imposed restrictions, but we still do not know if the cod will come back in their previous numbers.

The amount of cod caught in the Grand Banks (North Atlantic) fisheries (1851–2014).

Figure 20.3 The amount of cod caught in the Grand Banks (North Atlantic) fisheries (1851–2014).

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. 2005. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis. Washington, DC: Island Press.

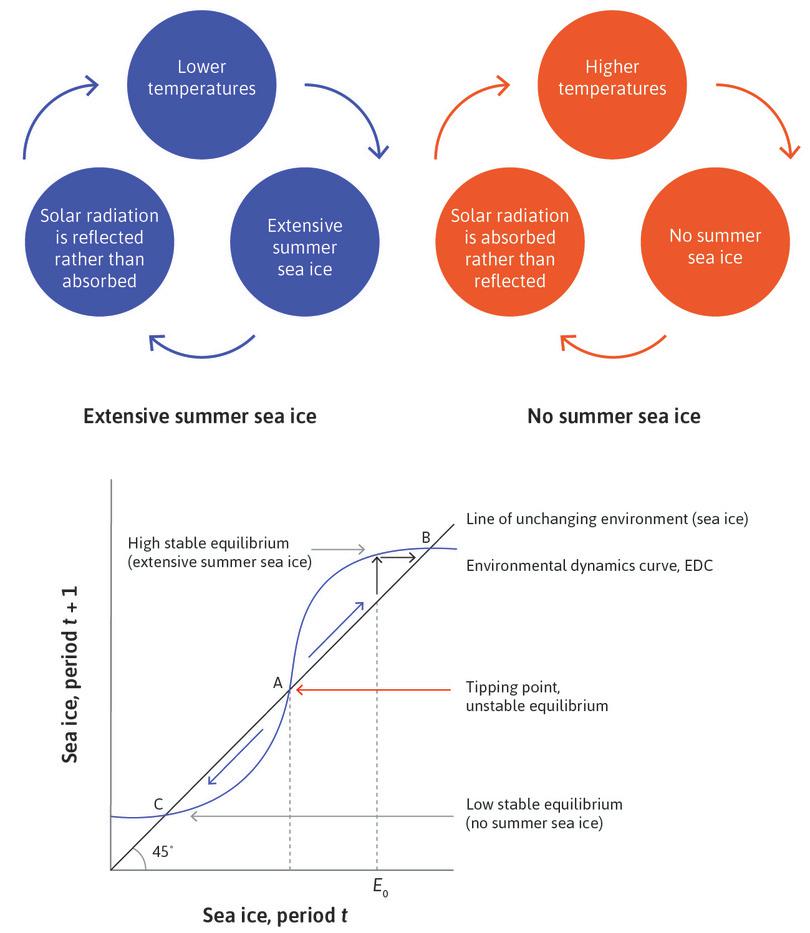

- positive feedback (process)

- A process whereby some initial change sets in motion a process that magnifies the initial change. See also: negative feedback (process).

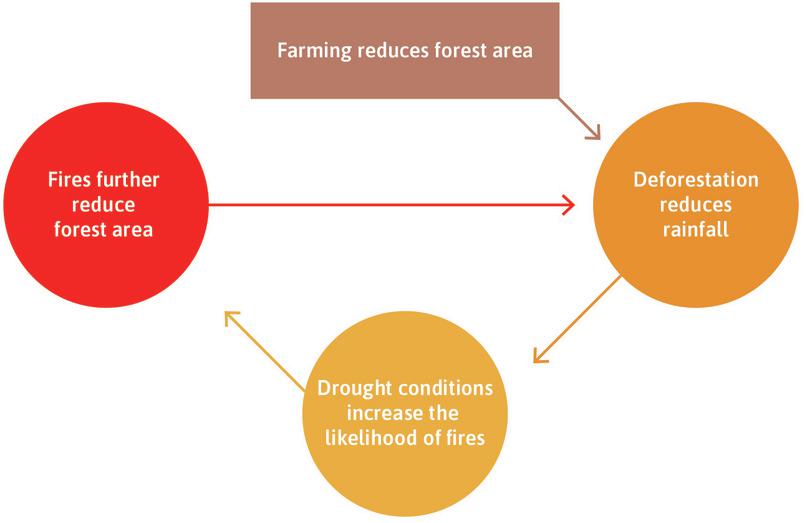

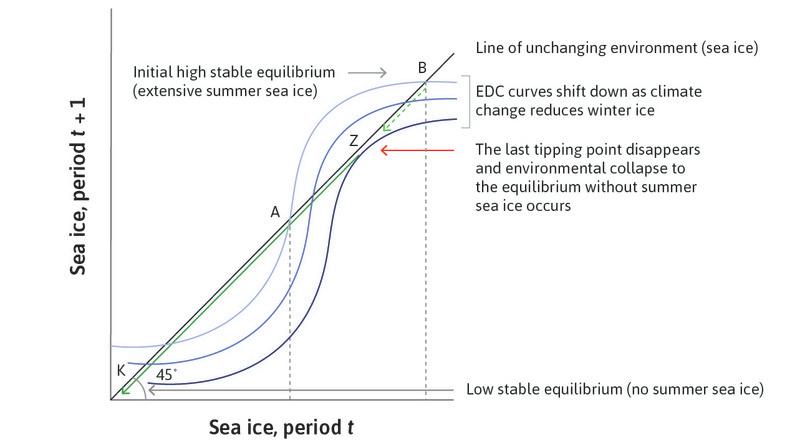

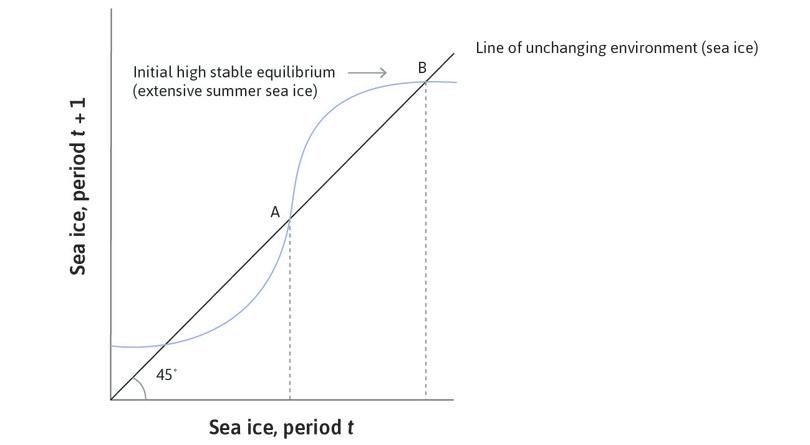

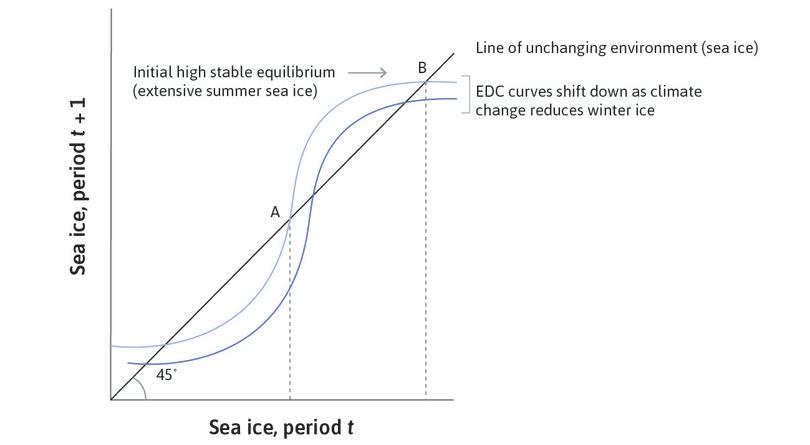

Rapid changes like the Grand Banks cod disappearance are referred to as ecosystem collapse, and result from environmental vicious circles. In the Amazon, for example, change may become self-reinforcing due to the positive feedback processes illustrated in Figure 20.4. Past a certain level of deforestation, the process becomes self-sustaining even without further expansion of farming.

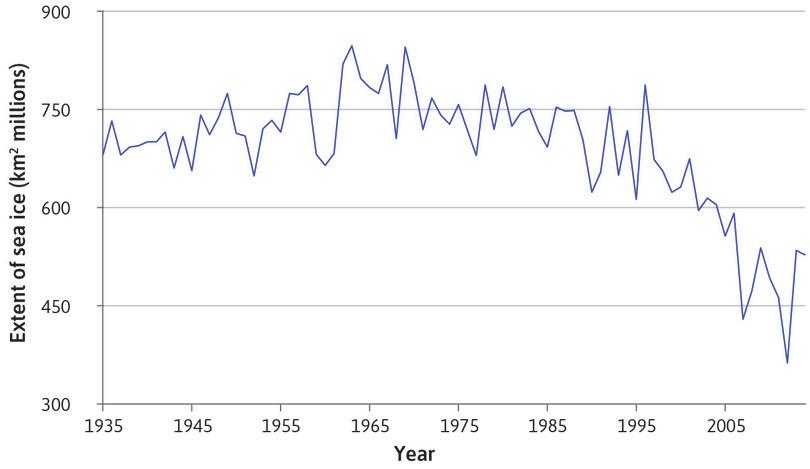

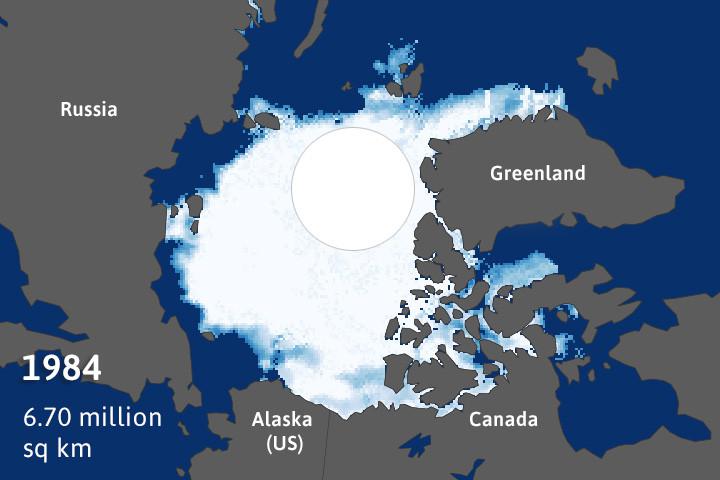

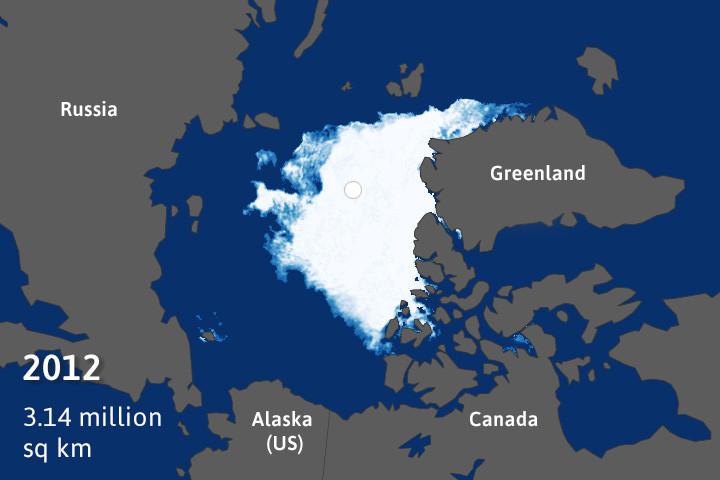

Similarly, the process of global warming can be self-reinforcing due, for example, to its impact on Arctic ice cover, as we will see later in Section 20.8.

The depletion of commodities and global warming are two aspects of environmental degradation. But we will see that there is also an important difference between the two: commodities are priced and traded, and so over-use of some resources may self-correct as prices of scarce commodites rise. Negative external environmental effects are usually only corrected through coordinated policy or political action, which is harder to achieve. This action has often been too little or too late, as we will see.

In the rest of this unit, we will show that environmental problems are as diverse as nature itself, and that understanding the economics of the environment will require you to employ not only the tools you have learned already, but also to study the interaction of physical and biological processes with human economic activity.

Question 20.1 Choose the correct answer(s)

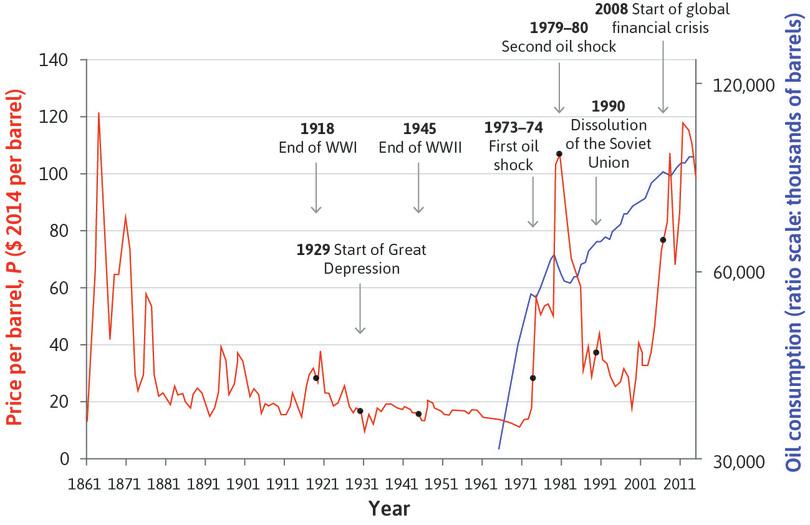

Figure 11.7 shows the world oil price (in 2014 prices) and global oil consumption.

You also have the additional information that the world reserves of oil more than doubled to 1.7 trillion barrels between 1981 and 2014. More than 1 trillion barrels were extracted and consumed in the same period. Based on this information, which of the following statements is correct?

- False. The 1970s oil shock was caused by a reduction of supply, not an increase in demand.

- False. The global financial crisis caused a fall in demand, rather than supply.

- False. Reserves increased by more than the amount extracted, suggesting that the increases in supply were greater than the increases in demand.

- True. Reserves increased by more than extraction. This is likely to be largely due to technological improvements that allowed more oil to be identified and economically extracted.

20.1 Recap: External effects, incomplete contracts, and missing markets

The study of environmental economics began in Unit 1 of this course, where we saw that economic activity (the production and distribution of goods and services) takes place within the biological and physical system. As we saw in Figure 1.5 and Figure 1.12, the economy is embedded within society, but also within the ecosystem. Resources flow from nature into the human economy. Waste, such as carbon dioxide (CO₂) emissions, or toxic sewage produced by firms and households, flows back into nature—mainly into the atmosphere and the ocean. Scientific evidence suggests that the planet has a limited capacity to absorb the pollutants that the human economy generates. In this unit, we investigate the nature of the global ecosystem, which provides the resources that feed economic processes and the sinks where we dispose of our wastes.

In Unit 4, we introduced environmental problems at a local level, among people who were similar in most respects. Anil and Bala were neighbouring landowners with a pest management problem. They could choose between an environmentally damaging pesticide and benign pest management systems. The outcome was inefficient and environmentally destructive because they could not make a binding agreement (a complete and enforceable contract) in advance about how they would act. In Unit 4, we also discovered that contributing to sustaining the quality of the environment is, to some extent, a public good, and that there are strong self-interested motives to free ride on the activities of others. So, while everyone would benefit if we all contributed to protecting the environment, we often do not do our part.

When small numbers of individuals interact, however, we saw that informal agreements and social norms (a concern for the others’ wellbeing, for example) might be sufficient to address environmental problems. Examples found in real life include irrigation systems and the management of common land.

In Unit 12, we expanded the scope of environmental problems to include two groups of people pursuing different livelihoods. We considered a hypothetical pesticide called Weevokil (based, again, on real-world cases) and its effects on fishing and the jobs of workers who produce bananas. In this case, there was a missing market—the plantation owners did not need to buy the right to pollute the fisheries, because they could do it for free. This is another case of an incomplete contract.

In cases like this, taxes can increase the polluter’s marginal private cost of production so that it equals the marginal social cost, resulting in the socially optimal level of production (and pollution). We canvassed a variety of solutions to the environmental problem (the external effects of the pesticide on the downstream fisheries), including bargaining between the organizations of fishermen and the plantation owners, and legislation (in the real-world case that inspired our Weevokil model, the government eventually banned the chemical).

Figure 20.5 reproduces a segment of Figure 12.8 that summarizes the nature of market failures in interactions between economic actors and the environment, and lists some possible remedies.

| Decision | How it affects others | Cost or benefit | Market failure (misallocation of resources) | Possible remedies | Terms applied to this type of market failure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A firm uses a pesticide that runs off into waterways | Downstream damage | Private benefit, external cost | Overuse of pesticide and overproduction of the crop for which it is used | Taxes, quotas, bans, bargaining, common ownership of all affected assets | Negative external effect, environmental spillover |

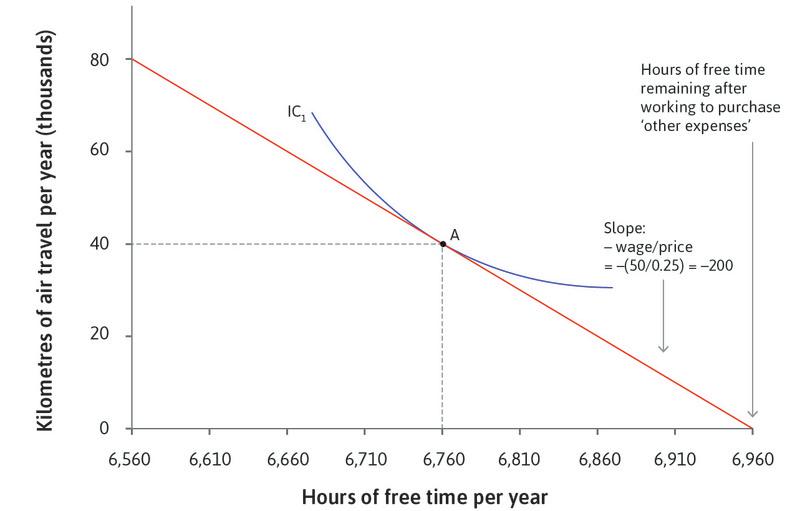

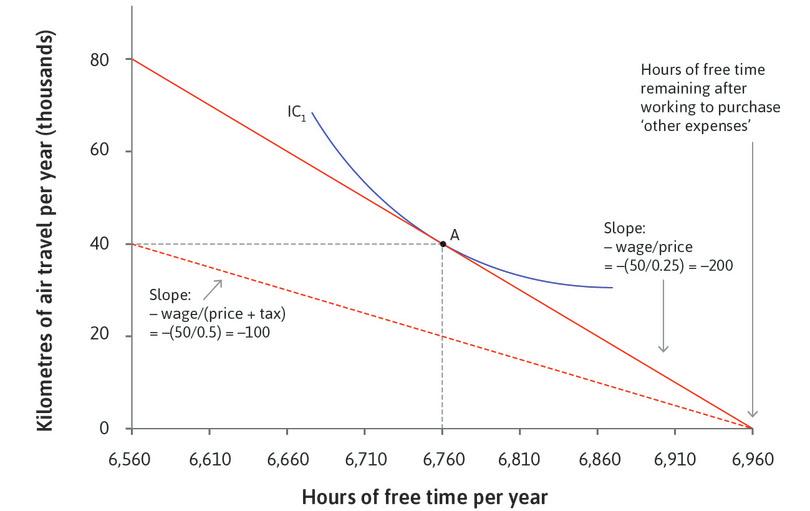

| You take an international flight | Increase in global carbon emissions | Private benefit, external cost | Overuse of air travel | Taxes, quotas | Public bad, negative external effect |

External environmental effects.

Figure 20.5 External environmental effects.

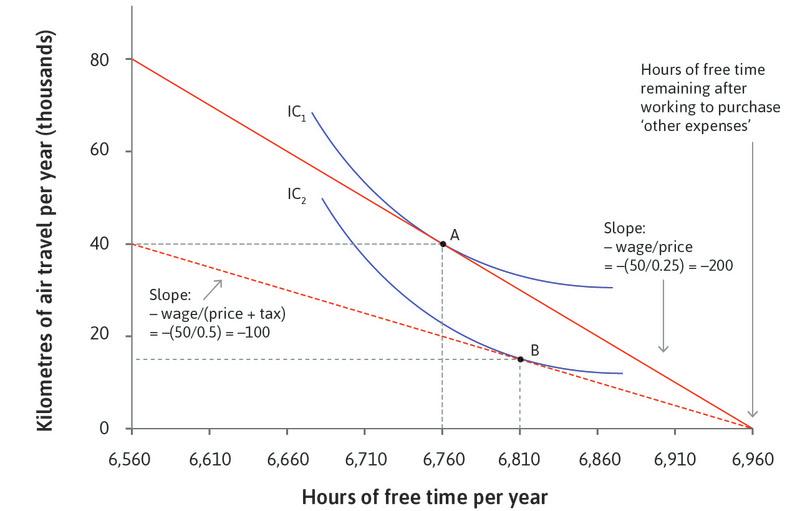

In this unit, we also consider the problem of climate change. Like the market failures above, climate change arises due to missing markets. However, unlike local environmental issues, climate change is global in scope. It involves people with vastly differing interests, ranging from those whose entire nation may be submerged by rising sea levels to those who profit from the production and use of the carbon-based energy that contributes to global climate change. We will see that many of the concepts developed already, such as feasible sets and indifference curves, apply in these cases as well.

The problem of climate change combines missing markets, uncertainty about its effect on the economy, the possibility of positive feedbacks and environmental tipping points, the need for international cooperation, and intergenerational issues. It is the greatest challenge of our time, and we need to use our entire toolkit (and more) to see how we can address it.

Question 20.2 Choose the correct answer(s)

Refer to Figure 20.5.

Based on this information, which of the following statements is correct?

- False. For instance, bargaining may not be effective when the number of people affected by the externality is very large. With climate change, those affected potentially includes everyone alive today as well as unborn future generations.

- True. The market price will not reflect the additional costs imposed on downstream fisheries.

- False. Negative externalities result in overuse, whereas positive externalities result in underuse.

- False. Insofar as additional taxes reflect the social cost of air travel (due to emissions, noise pollution and so on), the reduction in air travel is economically efficient.

20.2 Climate change

Many scientists now see climate change as the greatest threat to future human wellbeing. We focus on climate change because of its importance as an environmental problem, and because it illustrates the difficulties of designing and implementing adequate environmental policies. This problem tests our framework of efficiency and fairness to the limit, because of five features that climate change shares with other environmental problems:

- greenhouse gas

- Gases—mainly water vapour, carbon dioxide, methane and ozone—released in the earth’s atmosphere that lead to increases in atmospheric temperature and changes in climate.

- Stabilizing yearly emissions is not sufficient: Climate is affected by the total amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. This is increasing due to the annual flow of emissions. But merely stabilizing emissions at current levels will not be enough, because the stock of greenhouses gases would then continue to increase.

- Irreversibility of climate change: Increases in the amount of CO₂ in the atmosphere are partially irreversible, which means that our current actions have long-lasting effects on future generations.

- The worst-case scenario: Experts are uncertain about the scale, timing, and global pattern of the effects of climate change, but most agree that climate change could be catastrophic. Therefore, the most likely scenario should not be the only guide to policy. We need to take into account a range of possible scenarios, including some very unlikely but disastrous ones.

- A global problem requiring international cooperation: The contributions to climate change come from all parts of the world, and its effects will be felt by all of nearly 200 autonomous nations. It will be solved only by a high level of cooperation between the largest and most powerful nations, at a minimum, on a scale without historical precedent.

- Conflicts of interest: The impacts of climate change differ among people according to their economic circumstances, both across the globe and within countries. Future generations will experience the effects of today’s emissions, but also the actions we take to reduce them. It is unclear how to balance the competing interests of individuals in different economic circumstances, and the interests of current and future generations.

Climate change and economic activity

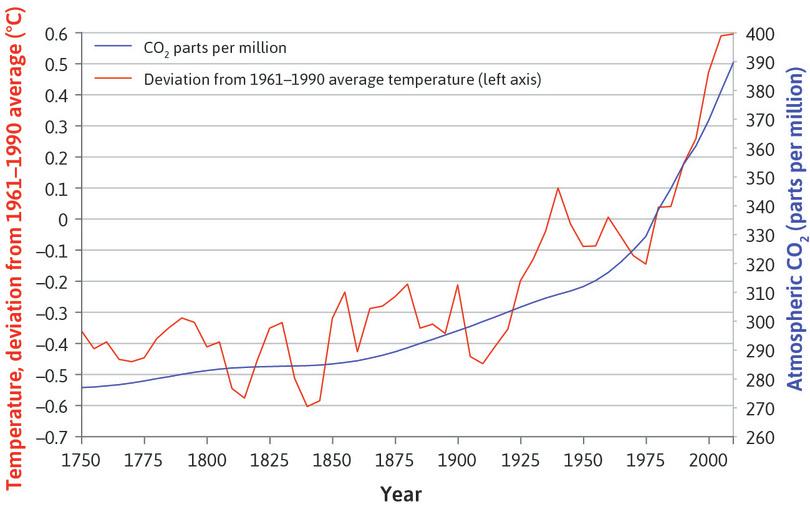

Figure 20.6 shows the data on the stock of CO₂ (in parts per million) using the right-hand scale, and global temperature (as the deviation from the average over the period 1961–1990) using the left-hand scale, for the period since 1750.

Global atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide and global temperatures (1750–2010).

Figure 20.6 Global atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide and global temperatures (1750–2010).

Years 1010–1975: David M. Etheridge, L. Paul Steele, Roger J. Francey, and Ray L. Langenfelds. 2012. ‘Historical Record from the Law Dome DE08, DE08-2, and DSS Ice Cores’. Division of Atmospheric Research, CSIRO, Aspendale, Victoria, Australia. Years 1976–2010: Data from Mauna Loa observatory; Tom A. Boden, Gregg Marland, and Robert J. Andres. 2010. ‘Global, Regional and National Fossil-Fuel CO2 Emissions’. Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center (CDIAC) Datasets. Note: This data is the same as in Figures 1.6a and 1.6b. Temperature is average northern hemisphere temperature.

Burning fossil fuels for power generation and industrial use leads to emissions of CO₂ into the atmosphere. These activities, together with CO₂ emissions from land-use changes, generate greenhouse gases equivalent to around 36 billion tonnes of CO₂ each year. Concentrations of CO₂ in the atmosphere have increased from 280 parts per million in 1800 to 400 parts per million, currently rising at 2–3 parts per million each year. CO₂ allows incoming sunlight to pass through it, but traps reflected heat on the earth, leading to increases in atmospheric temperatures and changes in climate. Some CO₂ also gets absorbed into the oceans. This increases the acidity of the oceans, killing marine life.

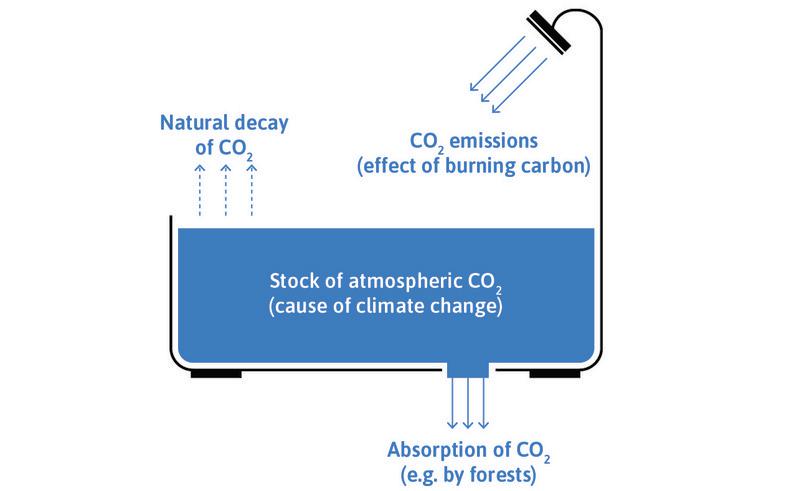

Figure 20.6 illustrates a key fact of climate science: that global warming is an effect of the amount of CO₂ and other greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. To use the language of Unit 10, where we discussed income (a flow) and wealth (a stock), climate change is caused by the stock of atmospheric greenhouse gases, not by the flow of our annual emissions. It’s what’s in the tub that matters. Figure 20.7 presents this new use of the bathtub model to illustrate the problem.

The increase in CO₂ in the atmosphere is occurring because the processes reducing the stock (natural decay of the CO₂ and absorption of CO₂ by forests) are far less than the new emissions that we add annually. Moreover, deforestation in the Amazon, Indonesia and elsewhere is reducing the CO₂ ‘outflows’ while also adding to CO₂ emissions. These forests are often replaced by agricultural activities that produce further greenhouse gas emissions in the form of methane releases from livestock and nitrous oxide releases from fertilizer overuse.

Martin Weitzman argues there is a non-trivial risk of a catastrophe from climate change in an EconTalk podcast.

The natural decay of CO₂ is extraordinarily slow. Of the carbon dioxide that humans have put in the atmosphere since the mass burning of coal that started in the Industrial Revolution, two-thirds will still be there a hundred years from now. More than a third of it will still be ‘in the tub’ a thousand years from now. The natural processes that stabilized greenhouse gases in the atmosphere in pre-industrial times have been entirely overwhelmed by human economic activity. And the imbalance is accelerating.

It is estimated that we can emit only a further 1 to 1.5 trillion tonnes of CO₂ into the atmosphere to give reasonable odds of limiting the increase in temperature to 2°C above pre-industrial levels. Should we manage to achieve this limit on emissions, there is still a probability of around 1% that temperature increases would be more than 6°C, causing a global economic catastrophe. If we exceed the limit and temperature rises to 3.4°C above pre-industrial levels, the probability of a climate-induced economic catastrophe would rise to 10%.1

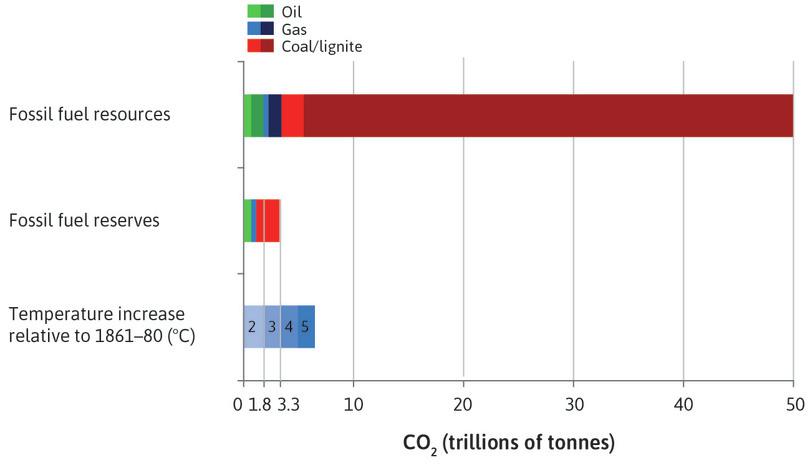

Figure 20.8 shows the relationship between estimated temperature increases and CO₂ emitted. It also shows the amount of CO₂ that would be emitted if we:

- reserves (natural resource)

- The amount of a natural resource that is economically feasible to extract given existing technologies. See also: resources (natural).

- burnt the fossil fuels that can be economically extracted at current prices and technology (reserves)

- burnt all fossil fuels in the earth’s crust (resources)

Figure 20.8 indicates that keeping the warming to 2°C implies that the majority of fossil fuel reserves and resources should remain in the ground.

Carbon dioxide contained in fossil fuel reserves and resources, relative to the atmospheric capacity of the earth.

Figure 20.8 Carbon dioxide contained in fossil fuel reserves and resources, relative to the atmospheric capacity of the earth.

Calculations by Alexander Otto of the Environmental Change Institute, University of Oxford, based on: Aurora Energy Research. 2014. ‘Carbon Content of Global Reserves and Resources’; Bundesanstalt für Geowissenschaften und Rohstoffe (The Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources). 2012. Energy Study 2012; IPCC. 2013 Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; Cameron Hepburn, Eric Beinhocker, J. Doyne Farmer, and Alexander Teytelboym. 2014. ‘Resilient and Inclusive Prosperity within Planetary Boundaries’. China & World Economy 22 (5): pp. 76–92.

Exercise 20.1 Assessing the economic impacts of global warming

In 1896, Swedish scientist Svante Arrhenius estimated the impact of doubling CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere, and later suggested that ‘the colder regions of the earth’ might want to burn more coal so as to enjoy a ‘better climate’.

In the next century, entire countries may disappear as the level of the oceans rise in response to the melting of the West Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets.

Find out what you can about which regions, industries, occupations, firms, or cities are likely to be:

- most positively affected by climate change

- most negatively affected by climate change

What are the main reasons why the effects of climate change differ across these groups?

Exercise 20.2 Climate change causes and evidence

Use information from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration web page on climate change, and the latest report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change to answer the following questions:

- Explain what climate scientists believe to be the main causes of climate change.

- What evidence is there to indicate that climate change is already occurring?

- Name and explain three potential consequences of climate change in the future.

- Discuss why the three consequences you have listed may lead to disagreements and conflicts of interest about climate policy. (Hint: You may find it useful to draw on your answers to Exercise 20.1 about the winners and losers from climate change.)

Question 20.3 Choose the correct answer(s)

Figure 20.8 shows the temperature increase arising from the CO2 emitted, generated at different levels of use of fossil fuel reserves (which can be technically and economically extracted) and resources (estimated total amounts) in the earth’s crust. For example, it states that a further 1 to 1.5 trillion tonnes of CO2 emissions would be likely to lead to a 2°C increase in temperature, compared to the pre-industrial average.

You are also given that 36 billion tonnes of CO2 are generated each year currently. Based on this information, which of the following statements is correct?

- False. Whether we should stop using coal depends on the costs of further temperature increases relative to the benefits of coal use.

- False. Temperatures would increase by 3°C if we used all fossil fuel reserves.

- False. 1 to 1.5 trillion tonnes of CO2 emission would be likely to lead to a 2°C increase in temperature. However, larger increases in temperature are possible due to uncertainty concerning the link between emissions and temperature.

- True. Stabilizing emissions will cause a constant increase in the stock of CO2 in the atmosphere, leading to further temperature increases.

20.3 The abatement of environmental damages: Cost-benefit analysis

- abatement policy

- A policy designed to reduce environmental damages. See also: abatement.

Like other environmental problems, climate change can be addressed by environmental damage abatement policies such as:

- discovering and adopting technologies that are less polluting

- choosing to consume fewer or less environmentally damaging goods

- banning or limiting the use of environmentally harmful substances or activities

However, the economic costs of immediately eliminating all CO₂ emissions would surely exceed the environmental benefits. But what level of environmental abatement should be adopted instead?

This is in part a question about the facts: What is the trade-off between the benefits of producing and consuming more, and the enjoyment of a less-degraded environment? It is also an ethical question: how should we value environmental quality? How should we trade off consumption now, with environmental quality enjoyed both by current and future generations?

If we ask citizens about their views of proposed environmental policies, we expect their responses will differ, partly because a deteriorating environment affects different people in different ways. Your point of view may depend on whether you work outdoors (you will benefit more from a less polluted local environment) or in fossil fuel production (you may lose your job if the higher abatement costs levied on your firm causes it to shut down). It may depend on whether you have no choice but to live near a source of air pollution, or are wealthy enough to have a second home in the countryside.

Your opinion about how much we should spend today to protect future environments would no doubt differ from the values of those who make up the distant future generations that would be affected by our choices, if we could ask them. People’s views are strongly influenced by their self-interest but, as you would expect from the behavioural experiments in Unit 4, not totally so. We worry about the effect on others, even complete strangers.

For simplicity, we begin by setting aside these differences and consider a population composed of identical individuals. We ignore future generations, or optimistically assume that we will all live forever. We will begin by also assuming that everyone enjoys (or suffers from) the same level of environmental quality. Later in this unit we will look at what changes when we do not make these assumptions.

We will also start off with what we call the ‘ideal policymaker’ who seeks to serve the citizens’ interests.

How can economics help the policymaker determine the level of environmental quality that we would like to enjoy, knowing that people may have to consume less so they can enjoy a better environment? The first thing to think about is the actions that we can take and their consequences: the feasible set of outcomes.

To do this, we need to consider the ways that the resources of the society could be diverted from their current uses to reduce the environmentally degrading effects of economic activity. The nation may adopt policies to limit environmental damage. We refer to such policies as abatement policies, since they abate (reduce) pollution and environmental damage. The amount of reduction in emissions caused by these policies is referred to as the quantity of abatement. Abatement policies include taxes on emissions of pollutants, and incentives to use fuel-efficient cars.

In the rest of this section, we use a specific example to illustrate the general approach to environmental cost-benefit analysis. The specific case is the choice of global policies that reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Keep in mind that we are assuming that the policymakers throughout the world are able to implement these policies.

Abatement costs and the feasible set

- global greenhouse gas abatement cost curve

- This shows the total cost of abating greenhouse gas emissions using abatement policies ranked from the most cost-effective to the least. See also: abatement policy.

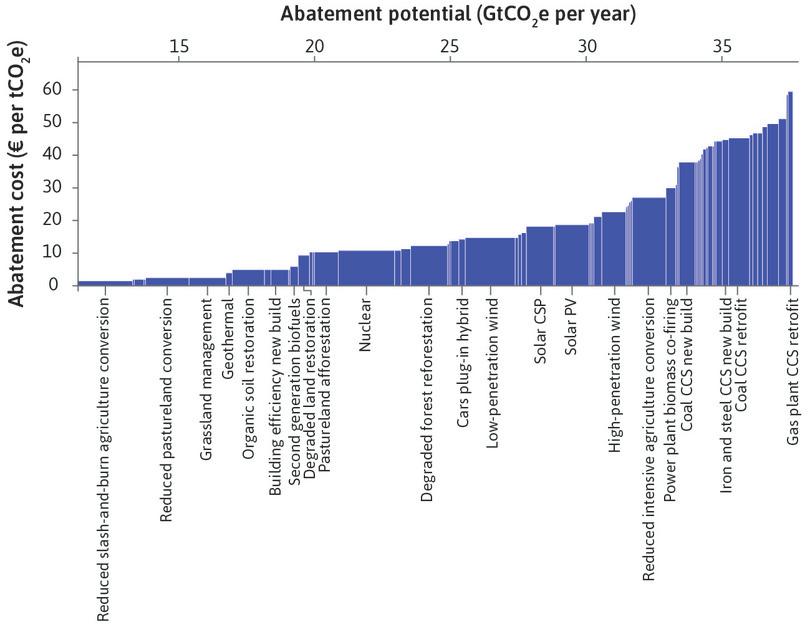

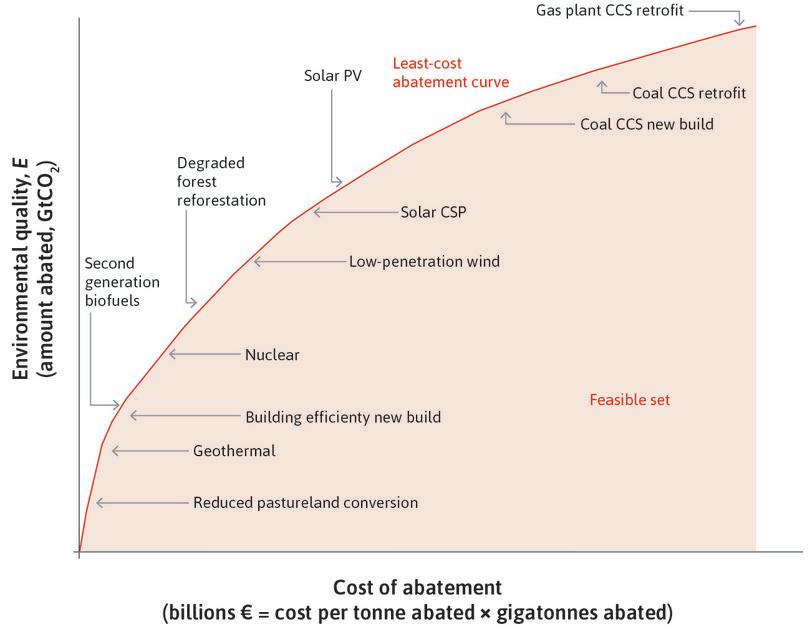

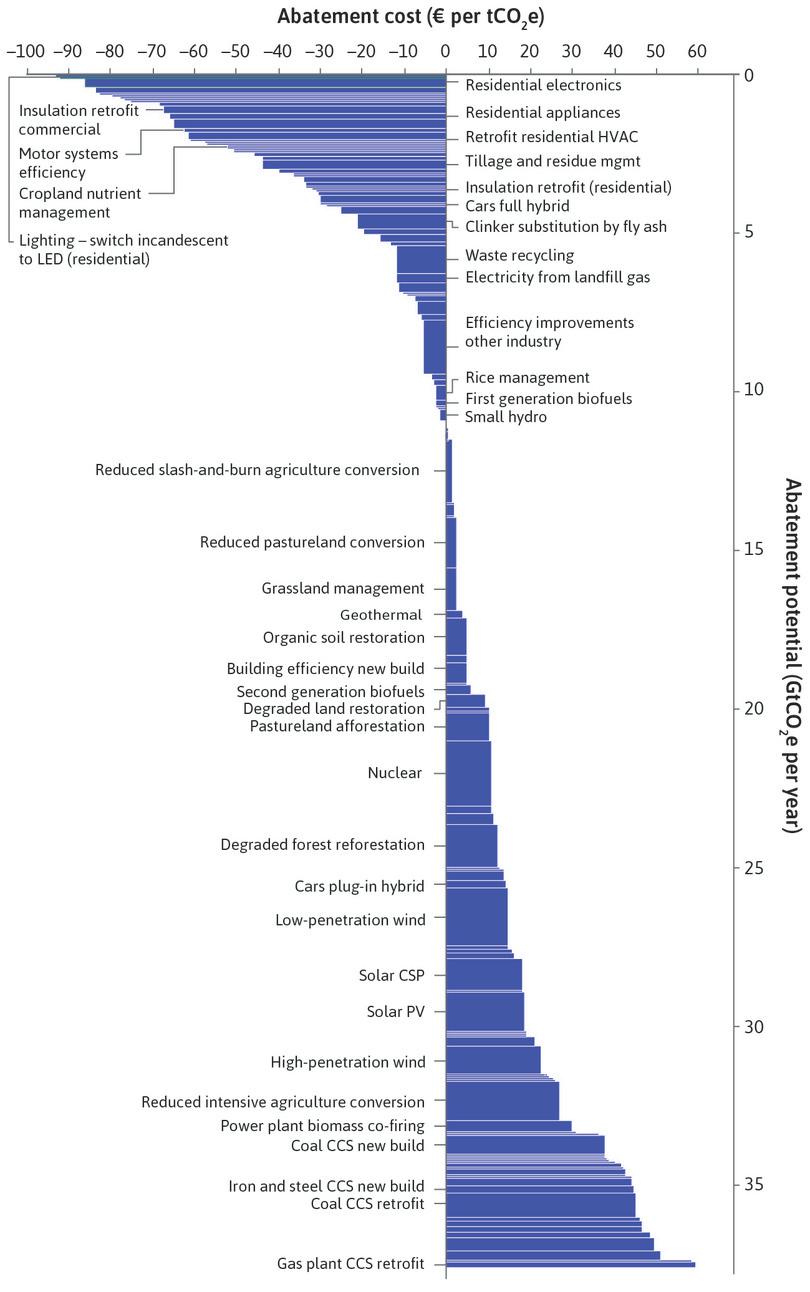

To get some idea of how economists assess abatement policy options, we look at the estimated cost of reduction of global greenhouse gas emissions in Figure 20.9, which shows the relationship between potential abatement and the cost of abatement per tonne. It is the marginal cost curve for the good, which we refer to as the global greenhouse gas abatement cost curve. These estimates were made by the consultancy firm McKinsey.

The measure of potential abatement, gigatonnes (10⁹ tonnes) of carbon dioxide equivalent (GtCO2e), is a unit used by the UN climate change scientific panel, the IPCC, to measure the effect of a technology or process on global warming. It expresses how much warming a given type of greenhouse gas would cause by using the equivalent amount of CO2 emissions that would have the same effect.

Each bar represents a change that could reduce carbon emissions. The height shows the cost of using the technology to reduce carbon emissions, in terms of euros per tonne of reduced CO₂ emissions. The width shows the reduction of CO₂ emissions, compared to the level without policy intervention. Therefore, for each method, a short bar means that there is a lot of abatement per euro spent. A wider bar means that this method has a higher potential to abate emissions.

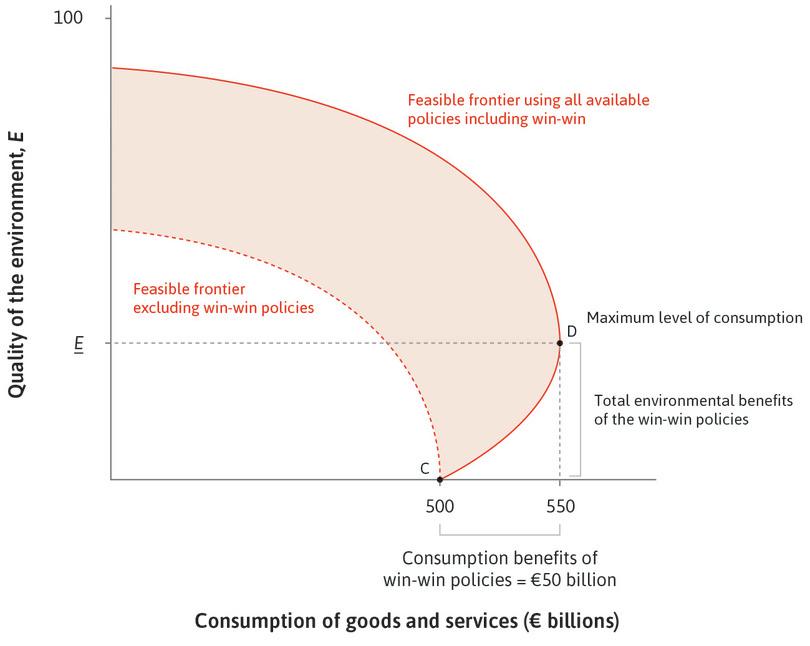

Note that in this figure we have only included policies which have a cost. There are many other policies that are win-win, because they both reduce carbon emissions and save money, such as fitting insulation in older houses. The full range of policies can be seen in Figure 20.26; the costly ones are in Figure 20.9. We discuss the implications of win-win policies in Section 20.10. You may wish to read that section now before working through the rest of the unit.

The cost of potential global greenhouse abatement in 2030 (compared with business as usual), using different policies.

Figure 20.9 The cost of potential global greenhouse abatement in 2030 (compared with business as usual), using different policies.

McKinsey & Company. 2013. Pathways to a Low-Carbon Economy: Version 2 of the Global Greenhouse Gas Abatement Cost Curve. McKinsey & Company.

In Figure 20.9, we order the policies from those with the least cost per tonne of CO₂ abated on the left to the highest cost per tonne abated on the right. By this measure, abating carbon emissions through changes in agriculture is the most efficient method, if we disregard the win-win policies. Nuclear, wind, and solar photovoltaics are all moderately efficient. At the time these estimates were produced, retrofitting gas-fired power plants for carbon capture and storage is the highest-cost policy per tonne of CO₂ abated. Together, the bars form a marginal cost curve, showing the cost of an additional tonne of abatement at any given level of abatement, assuming that we adopt the most efficient technologies first.

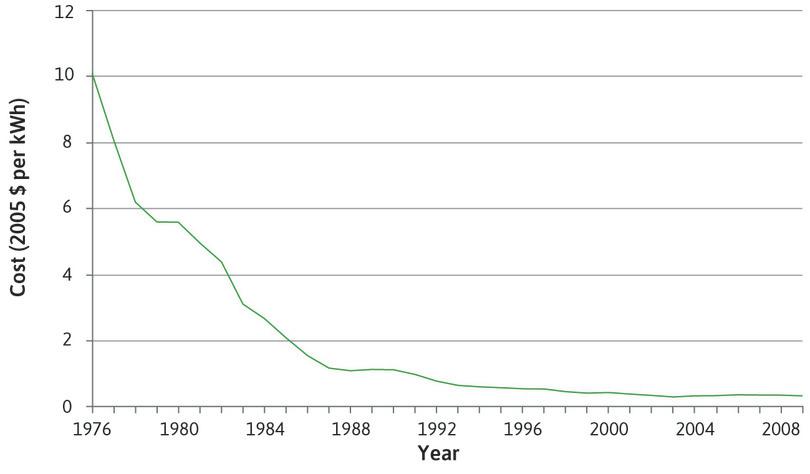

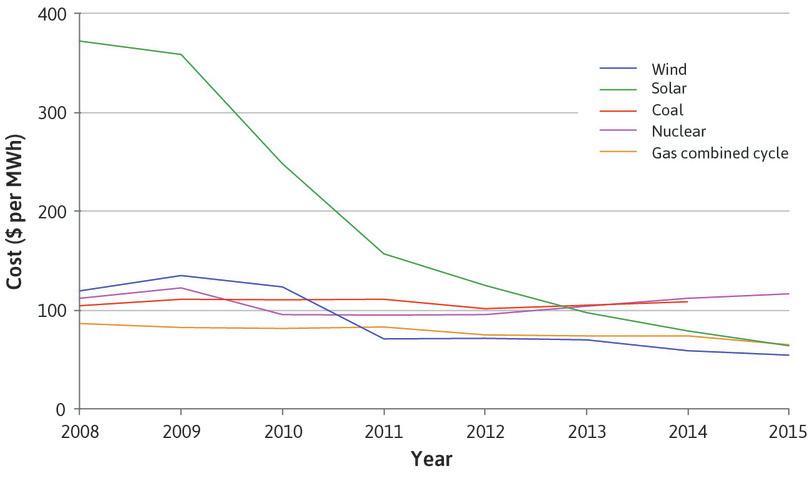

The science in this field is young, and technologies are continuously developing. As knowledge advances, the estimated abatement cost curve will change—indeed, it is likely to have changed already from the data shown here, which was published in 2013. For instance, rapid reductions in costs of solar power are likely to increase the efficiency of solar abatement, and therefore reduce the height of the bars associated with solar energy (see Figure 20.19a).

But even focusing on only the most efficient bars, implementing any of these abatement policies would divert resources from the production of other goods and services: the opportunity cost of an improved environment would be reduced consumption.

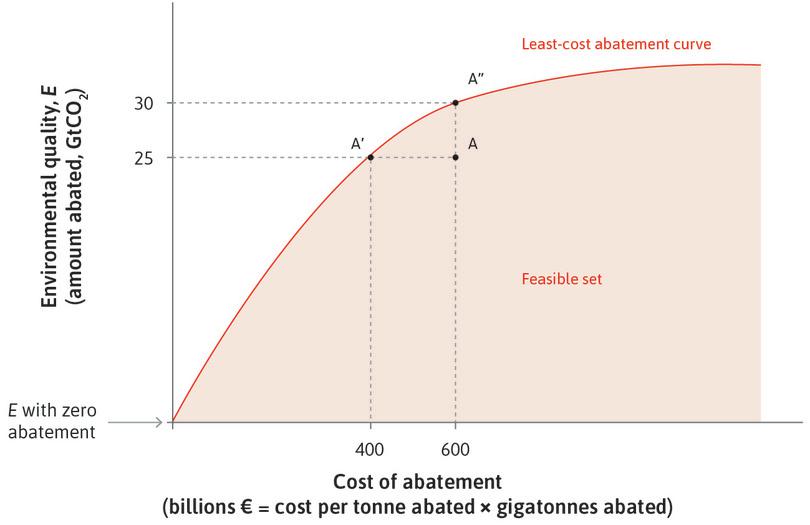

We can use data from the marginal cost curve for abatement (as in Figure 20.9) to estimate how much abatement we get for any level of expenditure, assuming we implement the most efficient methods first. These calculations are given in Figure 20.10. We would start by implementing the cheap and effective measures, such as land management and conversion policies. Having exhausted these policies, the curve becomes flatter at higher levels of expenditure, where we would be devoting more resources to less efficient methods such as carbon capture and storage (CCS) modifications to power stations. For more detail on the calculations of marginal abatement costs, see the Einstein at the end of this section.

The least-cost abatement curve: How total abatement (at least cost) depends on total abatement expenditures.

Figure 20.10 The least-cost abatement curve: How total abatement (at least cost) depends on total abatement expenditures.

McKinsey & Company. 2013. Pathways to a Low-Carbon Economy: Version 2 of the Global Greenhouse Gas Abatement Cost Curve. McKinsey & Company.

The curve in the figure, called the least-cost abatement curve, gives all the combinations of expenditures and resulting abatement when the lowest-cost changes are introduced first and the higher-cost ones are introduced later.

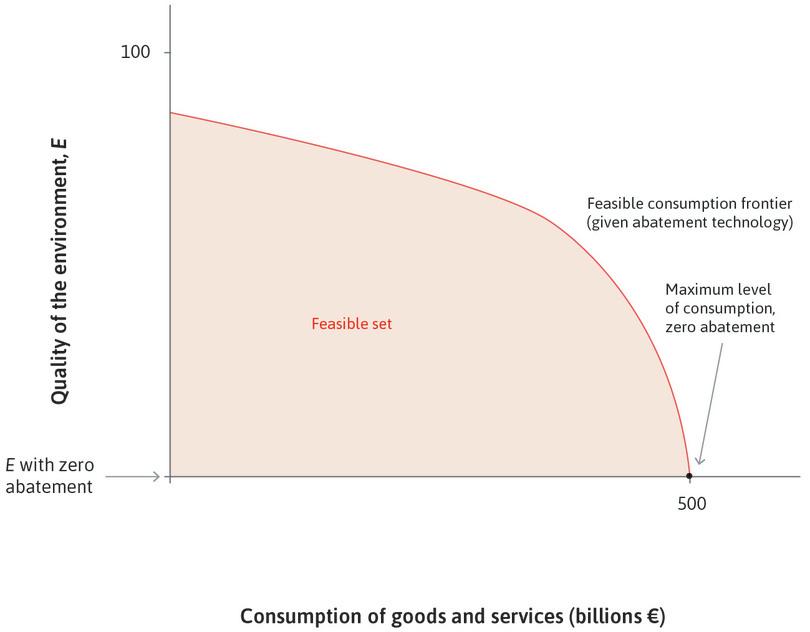

Using figures like 20.10, we can establish all of the possible combinations of consumption and abatement that are feasible. The available abatement technology is shown by the shaded set of points in Figure 20.11. In this figure, the horizontal axis measures the expenditure on abatement. The vertical axis measures environmental quality by the amount of abatement achieved. The zero point on the vertical axis is a situation in which no abatement occurs.

- dominated

- We describe an outcome in this way if more of something that is positively valued can be attained without less of anything else that is positively valued. In short: an outcome is dominated if there is a win-win alternative.

The shaded area is the feasible set of abatement expenditures and environmental outcomes. Points like A in the interior of the set are inefficient abatement policies. At A, we can see that there are alternative measures that would achieve the same level of abatement (25 gigatonnes) at lower cost (€400 billion rather than €600 billion). Similarly, for an expenditure of €600 billion, the choice of the most cost-effective abatement techniques would deliver 30 tonnes of CO₂ abatement and therefore higher environmental quality than at point A. Economists say that a point like A is dominated by points A′ and A″ and all the points in between. This means that at any of these other points there could be lower abatement costs and the same level of abatement (A′), or greater abatement at the same cost (A″).

How would an inefficient point like A in Figure 20.11 occur? In Figure 20.10, the policies were ordered so that the first expenditures on abatement are devoted to the most effective abatement policy. After exhausting the potential of each policy we moved to the next most effective policy.

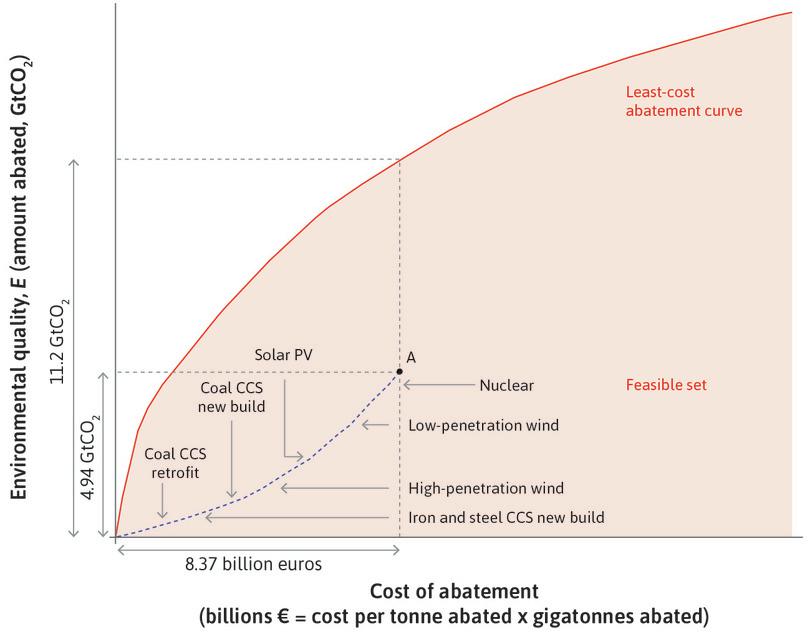

To highlight the difference between an efficient and an inefficient abatement policy, Figure 20.12 shows the abatement options based on the data in Figure 20.9, but with more costly policies adopted first. If a society has committed to spend €8.37 billion on abatement, and spends it all on coal carbon capture, nuclear, and other less effective options, then the least-cost abatement curve would be as shown in Figure 20.12.

We can see that if €8.37 billion were spent on abatement, the level of abatement would be 4.94 gigatonnes of CO₂, rather than the abatement of 11.2 gigatonnes that would have occurred if the society implemented least-cost policies, as shown in Figure 20.10.

Figures 20.10 and 20.12 send a clear message about priorities. If we have a limited amount to spend on abatement, and abatement technology does not change, focus on reducing pastureland conversion. According to Figure 20.10, we should also adopt nuclear power (assuming that waste storage and other security issues can be addressed), solar, and wind power before building new coal plants with carbon capture and storage (CCS), or retrofitting old coal plants for CCS.

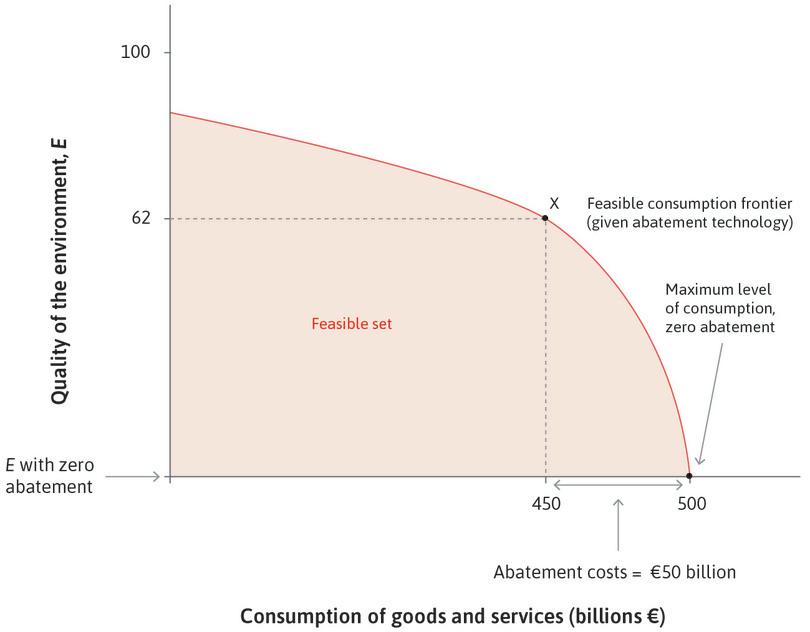

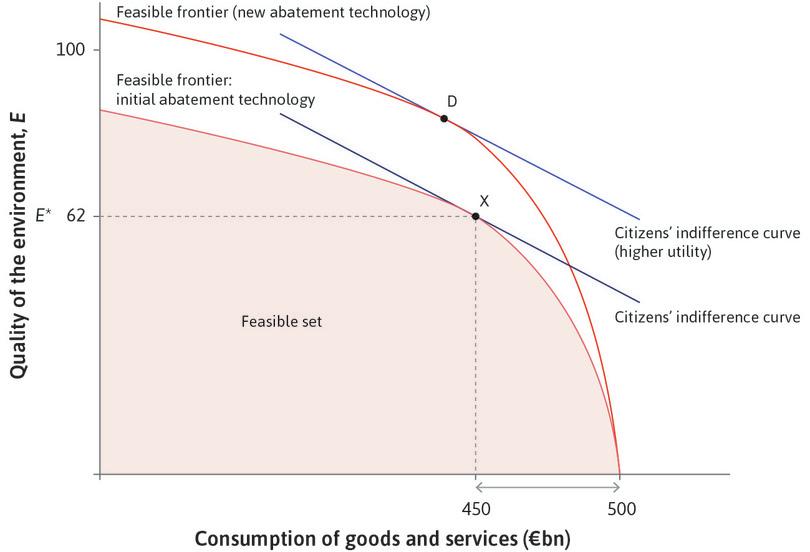

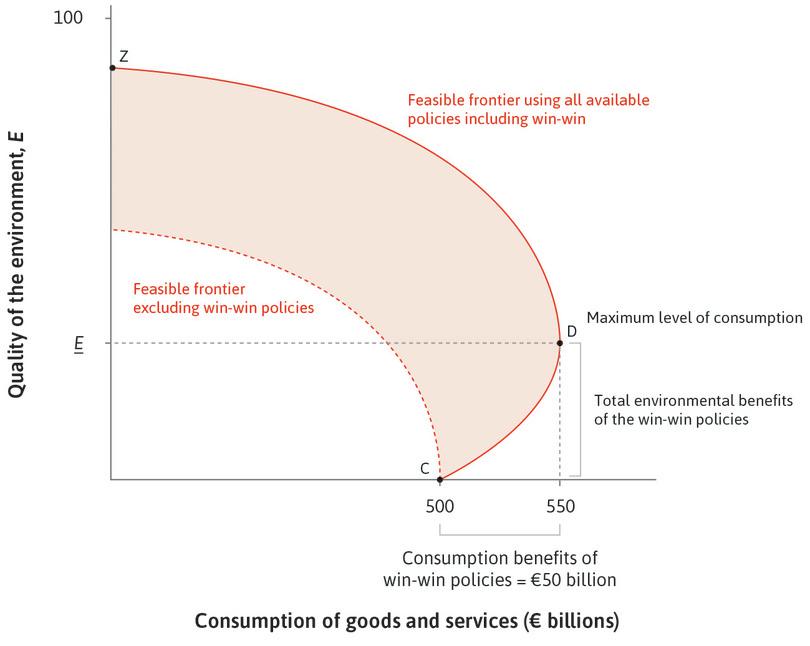

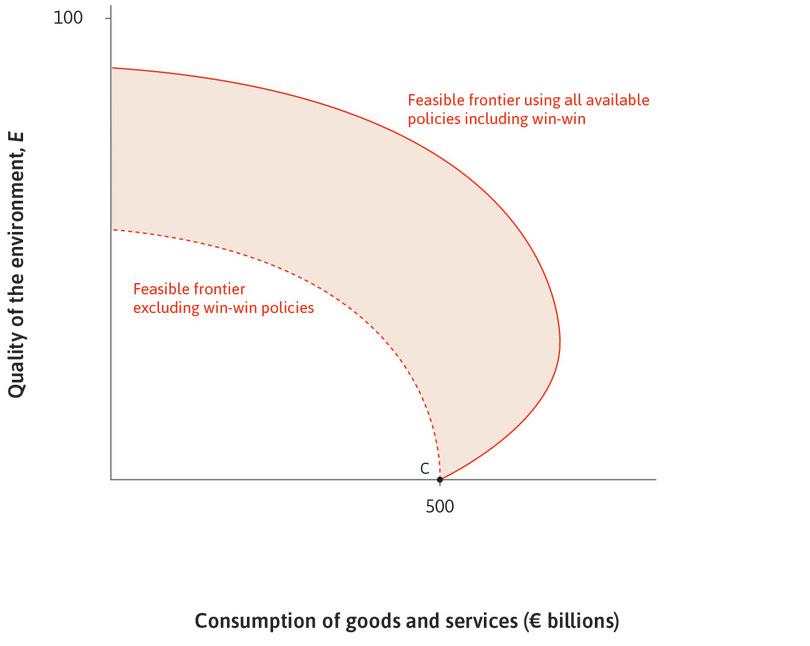

To study environment-consumption trade-offs, we invert the least-cost abatement curve, just as we did with the grain production function in Unit 3. Suppose that, after a given level of government expenditure on other policies and also a given level of investment, the maximum amount that people could consume in the economy if no abatement is implemented is €500 billion of goods and services. Then the feasible choices are the shaded portion of Figure 20.13.

In Figure 20.13, the vertical axis still measures the quality of the environment, but the horizontal axis now measures the goods available for consumption after abatement costs (from left to right). So, abatement expenditures are now measured from right to left.

The abatement choice problem now looks familiar. The policymaker wishes to select a point among the alternatives on the feasible frontier. Recall from the earlier units that the slope of the feasible frontier, also known as the marginal rate of transformation (MRT), is how much of the quantity on the vertical axis you would get by giving up one unit of the quantity on the horizontal axis. In the consumption-environment feasible frontier, this is the marginal rate of transformation of foregone consumption into environmental quality:

The steeper the feasible frontier (the greater the slope), the smaller the opportunity cost, in terms of foregone consumption, of further environmental improvements.

Environment-consumption indifference curves

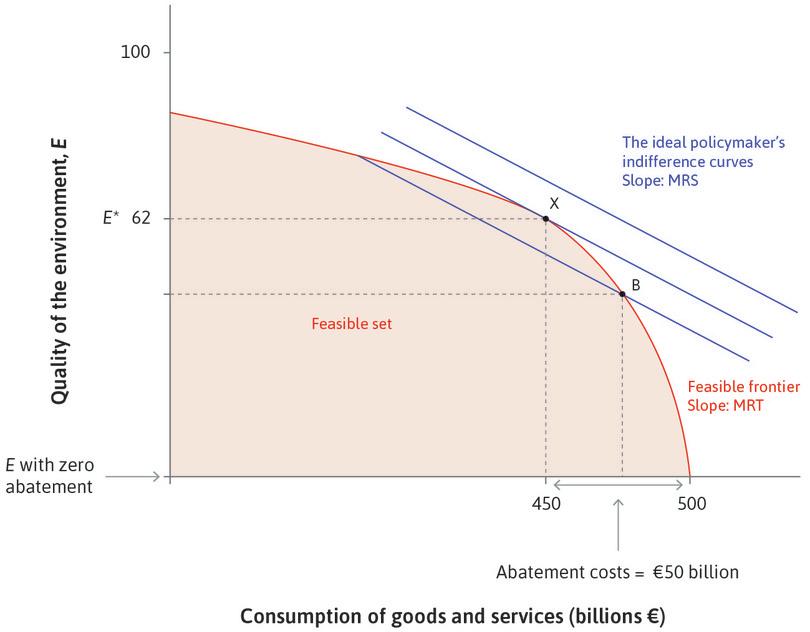

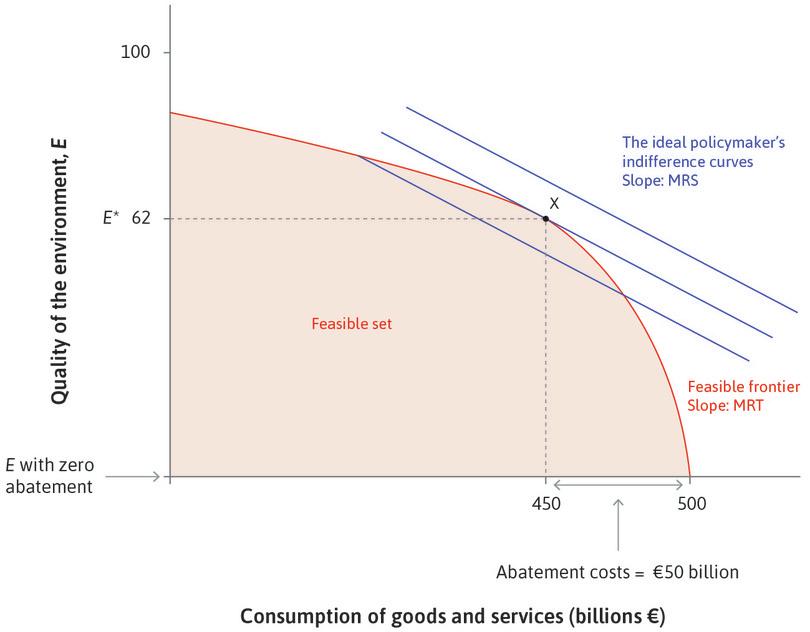

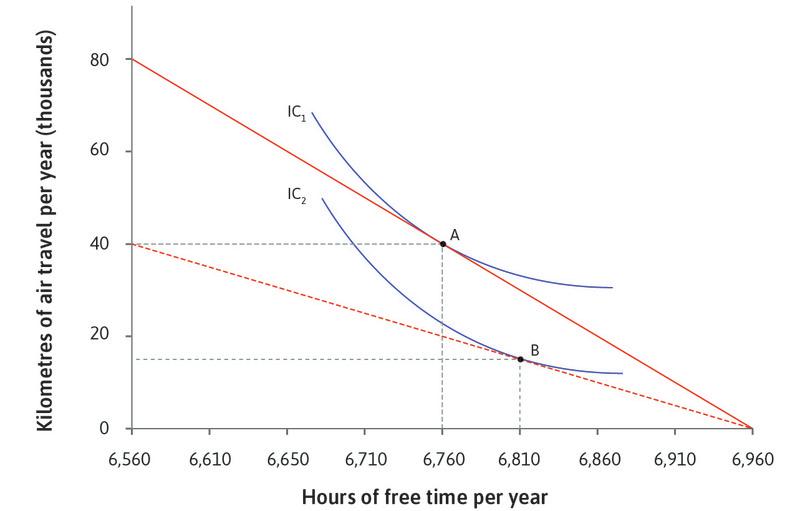

Which point on the feasible set will the policymaker choose? The answer can be found by studying the policymaker’s environment-consumption indifference curves in Figure 20.14, which show how much consumption citizens are willing to trade in exchange for better environmental quality.

We can write the slope of the indifference curve, the marginal rate of substitution (MRS) as:

The policymaker’s MRS will be high (a steep indifference curve) if consumption is valued highly by the citizens (a large marginal utility of consumption), and if citizens do not place a high value on additional abatement to improve environmental quality (marginal utility of abatement is low). Conversely, if the citizens value additional environmental quality highly relative to consumption, the MRS will be less steep.

In Figure 20.14, the indifference curves are straight lines because we have assumed for simplicity that the marginal utility of consumption and the marginal utility of environmental quality are both constant. That means they do not depend on the quantity of consumption or on the amount of abatement.

To think about how citizens’ preferences affect the optimal policy chosen, we suppose that the policymaker takes account of the preferences of all of the citizens, counting them equally. This means that if citizens decide to value environmental quality more, then the indifference curves of the policymaker will be flatter to reflect this.

Cost-benefit analysis: The ideal policymaker chooses an abatement level

Our policymaker uses two principles to make a decision about the level of abatement:

- She considers only abatement policies on the frontier of the feasible set: This eliminates higher-cost abatement policies that are inside the shaded area.

- She chooses the combination of environmental quality and consumption that puts her on the highest possible indifference curve.

To satisfy both conditions, she finds the point on the feasible frontier that equates the MRT (the slope of the feasible frontier) with the MRS (the slope of her highest possible indifference curve).

We can see from Figure 20.14 that point X is the level of environmental protection that the policymaker will wish to implement. The benefit indicated by the environmental quality index of 62 is achieved at a cost of reducing consumption by €50 billion and allocating it to abatement.

What would produce a different choice of abatement level?

- Different values: If the citizens cared less about the environment, then the indifference curves would be steeper than those in Figure 20.14, and the policymaker would choose a point like B, with higher consumption and lower abatement.

- Different costs of abatement: If abatement became cheaper than shown in Figure 20.14, then the feasible set would be steeper at each level of abatement. This would expand the production frontier upwards, implying that the policymaker would choose a higher level of abatement and lower consumption.

Exercise 20.3 Choosing abatement strategies

Look at the high-cost abatement strategies that we use to illustrate an inefficient abatement policy in Figure 20.12. Can you think of reasons why these policies might be introduced instead of the more cost-effective ones?

Exercise 20.4 Optimistic and pessimistic policies

In Figure 20.14, we described how a policymaker representing a uniform group of identical citizens chooses the optimal amount of abatement.

- Draw the indifference curves of the policymaker if she were to represent two different groups of citizens (again, we assume that all citizens in each group are identical, and the marginal utility of consumption and environmental quality are both constant). In the first group, citizens care more about environmental quality than consumption, and in the other group, citizens care more about consumption of goods and services. Explain why the optimal level of abatement costs will differ across groups.

- Now consider the example in the text of the abatement of global greenhouse gases. What are the main simplifications in the model that might lead the policy maker who uses this model to ignore important aspects of the problem of global greenhouse gas abatement?

In reality, there is uncertainty about the effectiveness of abatement expenditure and hence how costly abatement of environmental damage will be.

- On a new diagram, draw the feasible consumption frontier based on an optimistic assessment of the costs of abatement.

- Now draw the feasible consumption frontier based on a pessimistic assessment of the costs of abatement on the same diagram.

- By adding the policymaker’s indifference curves to your diagram in each case (assuming all citizens are identical), show how actual environmental quality chosen by the policymaker will differ, even if preferences are the same, depending on whether costs of abatement are assessed optimistically or pessimistically.

Question 20.4 Choose the correct answer(s)

Figure 20.9 shows a global greenhouse gas abatement curve, defined as the abatement in 2030 compared with ‘business as usual’, produced by McKinsey in 2015. The width of each bar indicates potential abatement measured in gigatonnes of CO2, while the height indicates the cost of abatement per tonne.

Based on this information, which of the following statements is correct?

- False. The ‘Nuclear’ bar is shorter than the ‘Solar PV’ or ‘Solar CSP’ bars, indicating a lower cost of abatement per tonne.

- True. The nuclear bar is wider, indicating greater abatement potential.

- False. The abatement potential is relatively small, but the cost per tonne abated is very low. It will therefore likely form one component of a least-cost mix of abatement opportunities.

- False. Solar energy is indicated in the diagram to be less efficient, in terms of abatement per euro spent. There may, however, be reasons unrelated to efficiency (such as safety) that justify preferring it to nuclear power.

Question 20.5 Choose the correct answer(s)

Figure 20.11 shows the graph of the amount abated against its total cost, under different abatement policies.

Based on this information, which of the following statements are correct?

- False. A is in the feasible set.

- False. A′ is lower cost but also has lower abatement. A″ is higher cost but achieves more abatement. In general, no point on the feasibility frontier is ever dominated.

- True. The diminishing slope indicates that the initial technologies adopted offer the most abatement per euro spent. Technically, the slope of this curve is the inverse of the marginal cost curve, therefore the decreasing slope indicates increasing marginal cost.

- False. The diminishing slope indicates that the technologies are being adopted in increasing order of their cost, so no higher curve can be attained.

Einstein Marginal abatement costs and the total productivity of abatement expenditures

How do we construct the line segments that define the boundary of the feasible set in Figure 20.10 from the data in Figure 20.9?

Let the height of the first bar (the most cost-effective abatement expenditure) in Figure 20.8 be y and the width of that bar be x. Then, in Figure 20.10:

- the initial slope of the curve is 1/y

- the horizontal axis value of the first point is xy

- this point’s vertical axis value is x

The other line segments making up the curve in Figure 20.9 are constructed in the same way.

20.4 Conflicts of interest: Bargaining over wages, pollution, and jobs

Conflicts of interest arise because environmental quality is never the same for everyone. Some people benefit or suffer more than others, depending on their location and income, as we saw in the banana pesticide case studied in Unit 12.

Here are two examples of how costs and benefits are not equally shared. In 2008 and 2009, two oil spills in the Niger River delta destroyed fisheries. The spills resulted from the oil extraction activities of the Anglo-Dutch company, Royal Dutch Shell. Lawyers for the Ogoni people, who suffered these external effects, brought a lawsuit against the Nigerian subsidiary of Shell in the British courts. In 2015, Shell settled out of court and paid £3,525 per person, of which £2,200 was paid to each individual, and the rest to support community public goods. This award amounted to more than most Ogoni people would earn in a year. Lawyers representing the community helped to set up bank accounts for the 15,600 beneficiaries.

The transfers may have compensated the Ogoni in part for the loss of a healthy environment, restoration of which the UN Environment Programme has estimated will cost $1 billion and take 30 years. For Royal Dutch Shell, the settlement at least partially internalizes the negative external effects of their activities, and might lead the company’s owners (and others extracting oil in the delta) to consider a change in their behaviour.

In 1974 a giant lead, silver, and zinc smelter owned by the Bunker Hill Company was the only major employer in the town of Kellogg, in the American state of Idaho, employing 2,300 people. Many children in the town developed flu-like symptoms. Doctors discovered that they were the result of high lead levels in their blood—high enough to impair cognitive and social development of children.

Three of the children of Bill Yoss, a welder at the smelter, had been found to have dangerously high levels of lead poisoning. ‘I don’t know where we’ll end up,’ he told a People reporter, ‘We may pull out of the state.’

The company refused to release its own tests of the smelter’s lead emission levels. Unless the state’s emissions regulations were relaxed, it said, the smelter would shut down, which it did, in 1981. Former employees looked for work elsewhere. The value of the homes and businesses in the town fell to a third of its earlier level. The local schools, which were supported by property taxes, did not have the funding to cope with those who remained.

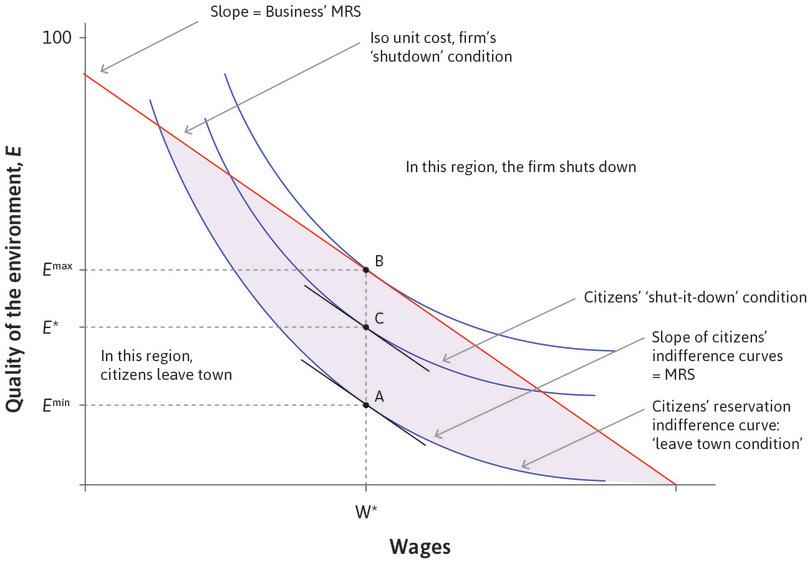

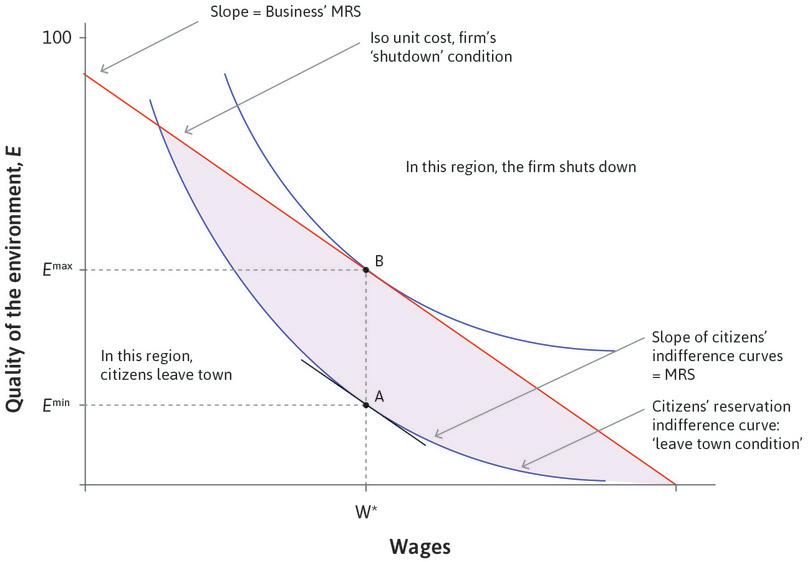

We model this problem by considering a hypothetical town, Brownsville, with a single business that employs the entire labour force but whose toxic emissions are a threat to the health of the citizens. The firm can vary the level of emissions that it imposes on the town, but the costs of implementing emissions capture and storage means lost profits. The single owner of the firm (who bears the costs of reducing the level of emissions) lives far enough away that the level of emissions he selects does not affect the quality of his environment. Therefore citizens and the business will have a conflict of interest over the level of emissions in the town, and also over the wages paid. You can think of the citizens as valuing ‘environmental quality’, which decreases when emissions increase and can be measured by an air quality index.

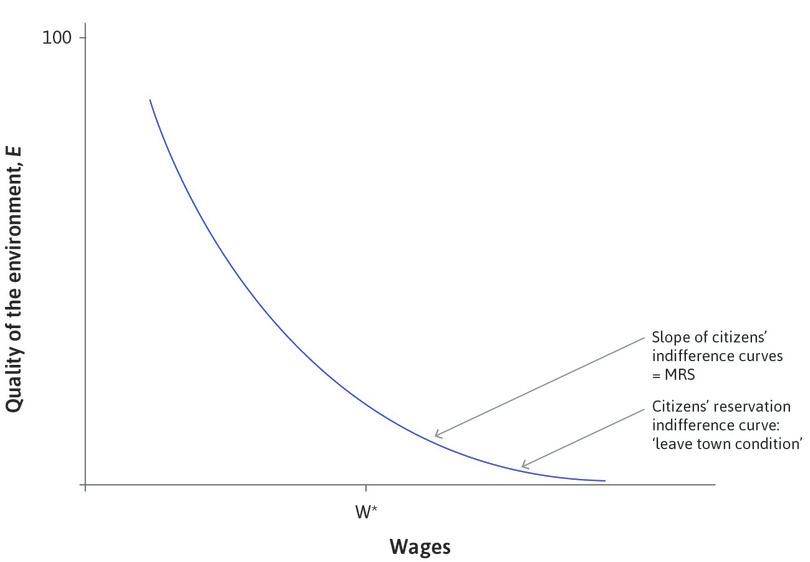

The citizens of the town have some bargaining power because each is free to leave Brownsville and seek employment elsewhere. So the business must offer them a package of environmental quality and wages that is at least as desirable as their reservation option, which is what they might expect to receive if they left Brownsville. We call this limit on what the business must offer the citizens the ‘leave town condition’.

The business owner has bargaining power, too, because the wage and environment package that he offers must result in profits high enough that the firm does not simply shut down or relocate (we call this the firm’s ‘shutdown condition’). The citizens cannot demand more than this wage, or they would be unemployed (remember there are no other firms in Brownsville). Thus the firm’s reservation option places limits on the bargain that the citizens can strike with the firm.

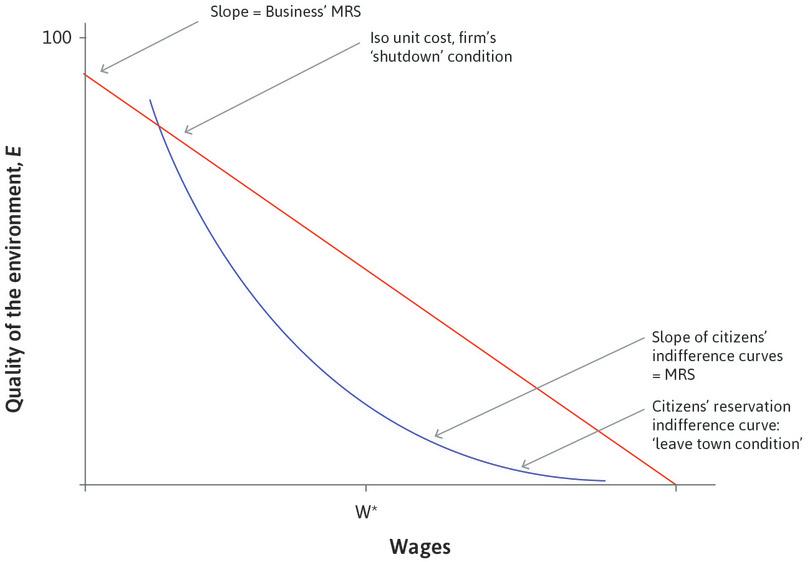

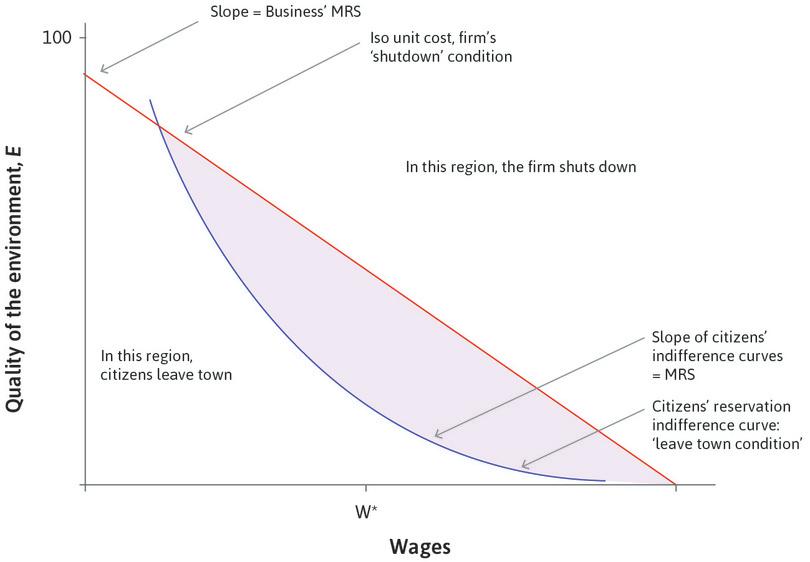

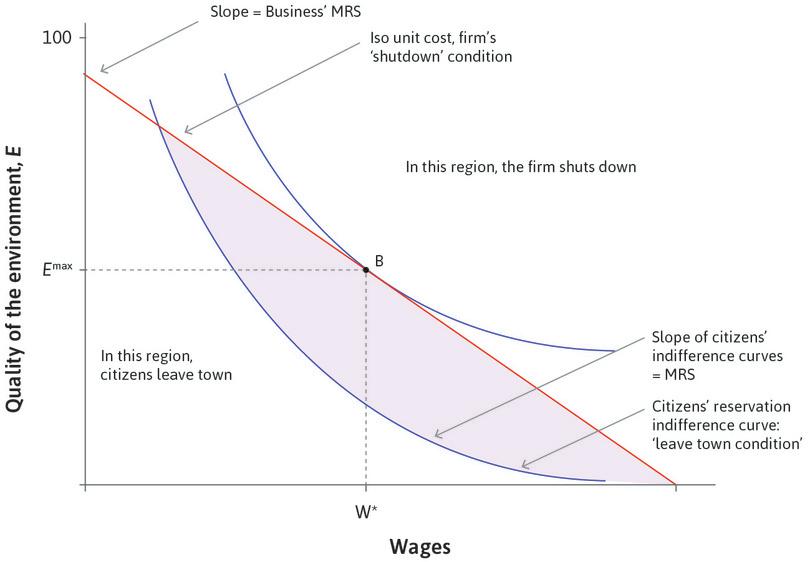

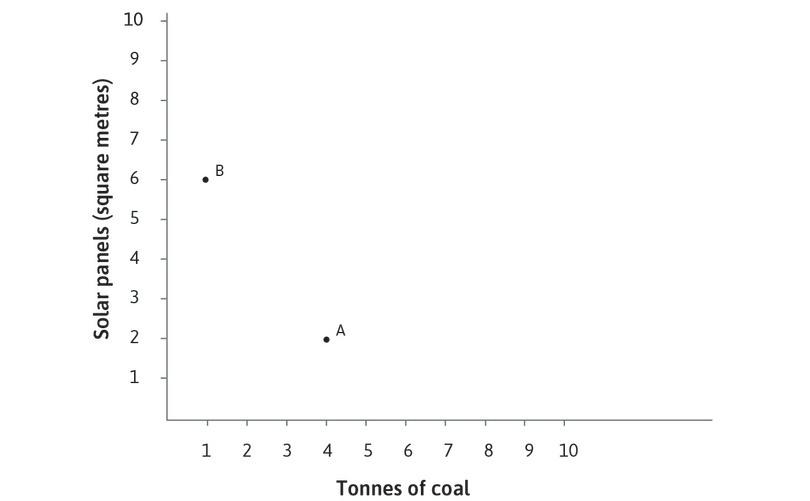

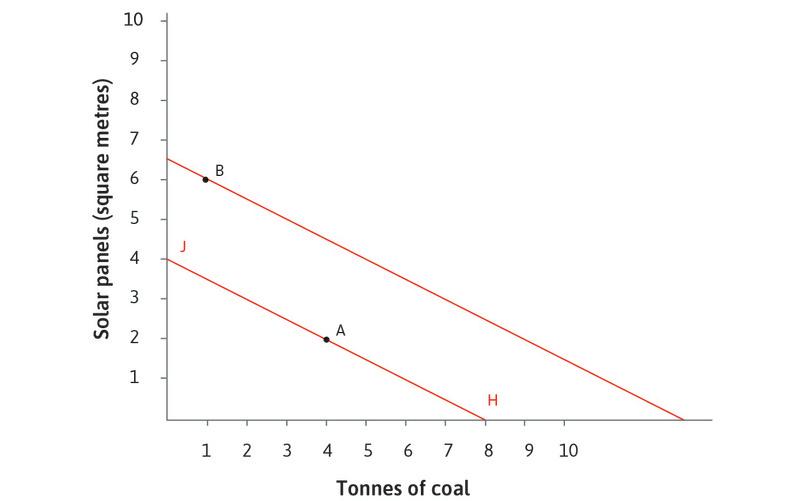

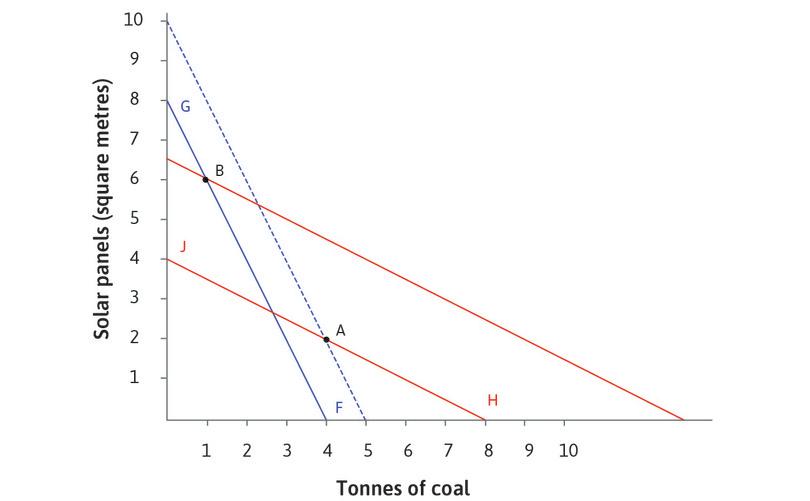

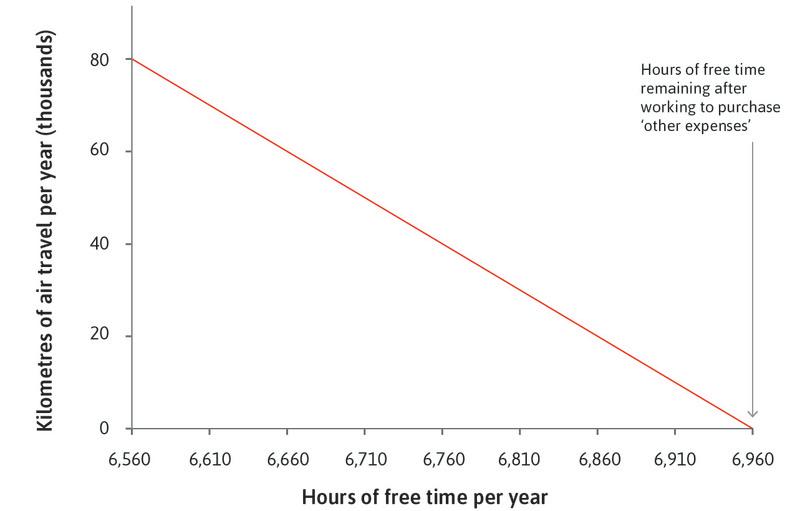

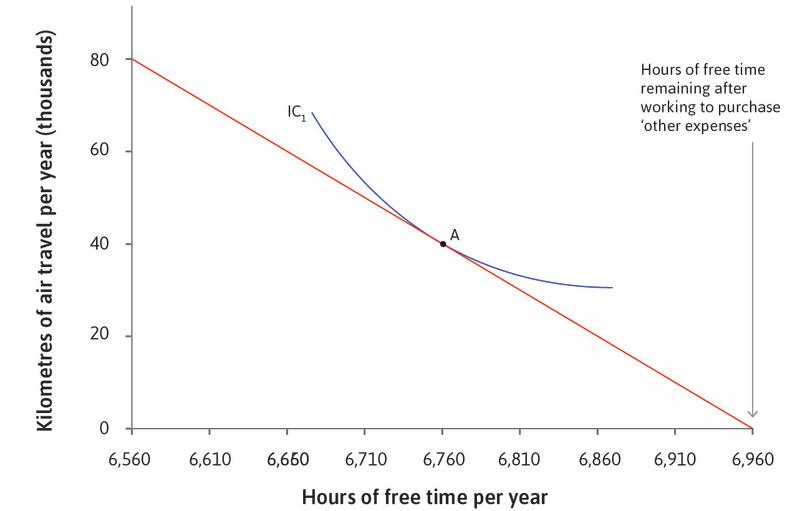

We represent the relationship between the business and the citizens in Figure 20.15. The wage paid to the employees of the firm is on the horizontal axis. The level of environmental quality experienced by the citizens is on the vertical axis. We make the following assumptions:

- Citizens are identical and so experience the same environmental quality.

- The owner is unaffected by the level of pollution: For him, the environmental external effects resulting from his decision about emissions are borne by others. Pollution for him is a private ‘good’, and he does not consume any of it.

Work through the analysis in Figure 20.15 to see how the choices of the citizens and businesses are modelled.

You may recall that this figure is very similar to Figure 5.8, in which Angela the farmer and Bruno the landowner were bargaining over the amount of grain Angela would transfer to Bruno. As in that problem, the study of a bargaining problem is easier if the slope of the indifference curves remains unchanged at a given wage as utility increases.

Here, the conflict is about the amount of emissions that the townspeople will suffer. The firm’s profits depend on the emissions, and profits are greater if it can dispose of more toxic materials freely.

The position of the citizens’ reservation indifference curve depends on what they would expect to get in some other location. If they could find a high-paying job in a non-toxic community, the curve would be higher and to the right of the one that is shown. Its slope, the marginal rate of substitution, is the citizens’ marginal utility of higher wages, divided by the marginal utility of environmental quality.

We assume that the citizens’ marginal valuation of improvements in the environment is constant, but (in contrast to the model in Section 20.3) they have diminishing marginal utility of receiving higher wages. At high wages (and very poor environmental quality) on the far right of the reservation indifference curve, the MRS is small (the curve is almost flat) because citizens would not care much about wages (as they are already getting paid a high wage) but they are very concerned about the poor environment. At low wages the curve is steep, because they place a high value on wage increases.

The firm’s shutdown condition shows the combinations of wages and environmental quality offered by the firm that would barely keep the firm in Brownsville. All of the points on this line have the same cost of producing a unit of output and, as a result, the same profit rate. The firm’s profits are increasing as you move towards the origin. It is like the isocost curve in Unit 2, and the isocost lines for effort in Unit 6.

The cost of raising the wage by $1 is $1. Assume the cost incurred by the owner if he reduces emissions is p per unit of abatement, so the owner’s MRS = 1/p. A steep line indicates that p is small—avoiding emissions and thereby allowing a healthier environment is cheap.

The firm faces a trade-off. If it is at point B in the figure, it pays wages and produces emissions at a level that makes it barely profitable enough to stay in business. Therefore, if it offers a higher-quality environment to the citizens, it can only do this by offering a lower wage. The opportunity cost of one unit of a better environment is p in reduced wages.

Any combination of wages and environmental quality in the shaded portion of the figure is a feasible outcome of this conflict. Any combination on the vertical line between A and B is a Pareto-efficient outcome. We cannot say which feasible outcome will occur, though, unless we know more about the bargaining power of the citizens and the firm.

The firm has all the bargaining power

If the firm could simply announce a take-it-or-leave-it ultimatum, then it would choose point A in Figure 20.15. The firm’s costs will then be well below the shutdown level of costs because they will be freely emitting toxic materials, which reduce the citizen’s environmental quality from Emax, the least emissions (and highest quality environment) consistent with the firm staying in business, to Emin. This difference (Emax − Emin) shows up as cost reductions, and hence as additional profits, in the firm’s accounts. It also shows up as exposure to health hazards in the medical records of the people who live in the town.

The firm’s chosen point, A, is on the citizens’ reservation indifference curve where the vertical distance between the firm’s shutdown condition and the citizens’ leave town condition is the greatest. This will occur when:

Citizens have all the bargaining power

If the bargaining power had been reversed, then the citizens would choose to impose Emax and wages w*. This ensures that the citizens are on their highest possible indifference curve, while also satisfying the firm’s shutdown condition. Again, at this point the MRS of the business is equal to the MRS of the citizens.

Dividing the mutual gains

The difference between Emax and Emin measures the extent of mutual gains the townspeople and the business may enjoy. Any outcome between A and B on the figure is preferable to the next best alternative for the business (shut down) and the citizens (leave town). You can think of the mutual gains as a pie that the citizens and the business owner will divide. How the pie is divided up between the two parties depends, as we have seen in Units 4 and 5, on their relative bargaining power.

A point such as C in Figure 20.15 might be possible if the citizens, acting jointly through their town council, imposed a legal minimal level of environmental quality and wages for the business to continue to operate. Acting together, the citizens would have more bargaining power than if they used the threat to leave town as individuals: they could require that the business at least meet the citizens’ ‘shut-it-down condition’ shown in Figure 20.15.

Bargaining power in this case would be affected not only by the two parties’ reservation options but also by:

- Enforcement capacity: The town government may not have enforcement capacities to impose an emissions limit on the firm.

- Verifiable information: The citizens may not have sufficient information about the levels and dangers of emissions to win a case in court. If so, the firm would not comply with an agreed-upon emissions level such as at C in Figure 20.15.

- Citizen consensus: If the town’s citizens were not in agreement about the dangers of the emissions, the elected officials of the town who legislate an emissions limit might not be re-elected.

- Lobbying: The firm may be able to convince the citizens that their health concerns were misplaced, or had little to do with the firm’s emissions.

- Legal recourse: The firm may be legally entitled to emit any level of emissions that it finds profitable (perhaps subject to having purchased permits allowing it to do this).

So far we have focused on the question of how much abatement there should be. Now we consider a second question: How should the desired level of abatement be accomplished?

Question 20.6 Choose the correct answer(s)

Consider a town with a single business that employs the entire labour force, whose toxic emissions are a threat to the health of the citizens. Figure 20.15 shows the business’ ‘shutdown’ curve (the combination of wages and environmental quality offered by the firm that would just about keep the firm operating) and the citizens’ indifference curves for the quality of environment and their wage income. The citizens’ reservation indifference curve is also shown.

Based on this information, which of the following statements is correct?

- True. At any of these points, at least one of the parties would prefer to take their outside option.

- False. Point A would be chosen, because it is the point that maximizes profits while satisfying the citizens ‘leave town condition’.

- False. Point B would be chosen, because it is the point that places citizens on their highest indifference curve while satisfying the firms ‘shutdown condition’. They strictly prefer B to the point where the ‘shutdown’ curve intersects the horizontal axis, which is the highest feasible wage.

- False. All points within the feasible set where the firm and citizen’s indifference curves are tangent are Pareto efficient (the line AB), including A, B, and C.

20.5 Cap and trade environmental policies

- price-based environmental policy

- A policy that uses a tax or subsidy to affect prices, with the goal of internalizing the external effects on the environment of an individual’s choices.

- quantity-based environmental policy

- Policies that implement environmental objectives by using bans, caps, and regulations.

In Unit 12, we saw possible remedies for the market failure that arose from the negative external effects of pesticide use. The range of remedies included private bargaining between the pesticide users and the fishing community whose livelihoods were threatened, taxes to make the pesticides (or the bananas produced using them) more expensive, ownership of all affected assets by a single business or other decision-making entity, and quotas or outright bans on the use of the pesticide. Some of these policies would have made it more expensive to harm the environment so as to provide incentives for greener economic decision making (price-based policies). Others would have made it illegal (quantity-based policies).

- cap and trade

- A policy through which a limited number of permits to pollute are issued, and can be bought and sold on a market. It combines a quantity-based limit on emissions, and a price-based approach that places a cost on environmentally damaging decisions.

A policy called cap and trade is a policy that combines a legal limit on the amount of emissions with an incentive-based approach to assigning the abatement required to meet this legal limit among firms and other actors.

Here is the idea:

- The government or governments set the total level of abatement required: This is called the ‘cap’ and it constitutes the ‘quantity’ side of the policy.

- The government creates permits: The number of permits issued limits total emissions to the size of the cap.

- The government allocates permits: They can be given to the firms operating in industries emitting the pollutant, or they can be auctioned to polluting firms by the government.

- The permits are traded: For some firms, polluting is very profitable and abatement costly. They will buy permits from other firms. Firms that produce little pollution or have low costs of abatement may have excess permits, which they can sell. Trade occurs until the gains from trade are eliminated.

- The firms submit permits to government to cover their emissions: For each tonne of emissions produced, firms are required to provide one permit to the government. Ideally, government monitoring ensures that firms cannot cheat, and any firms caught violating the law are penalized with large fines.

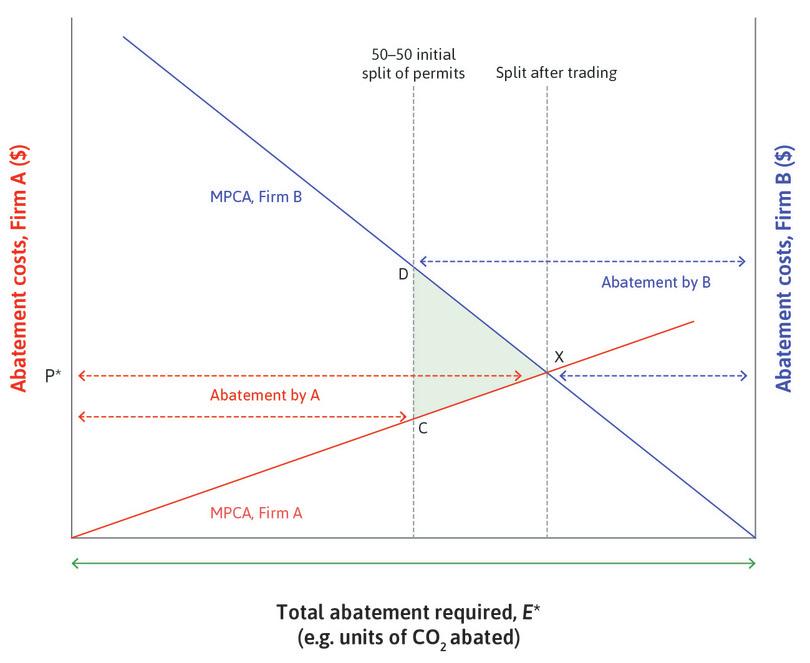

Cap and trade policies are a way of implementing some desired level of emissions (or, equivalently, the total level of abatement required, E*) as the ideal policymaker did in Figure 20.13.

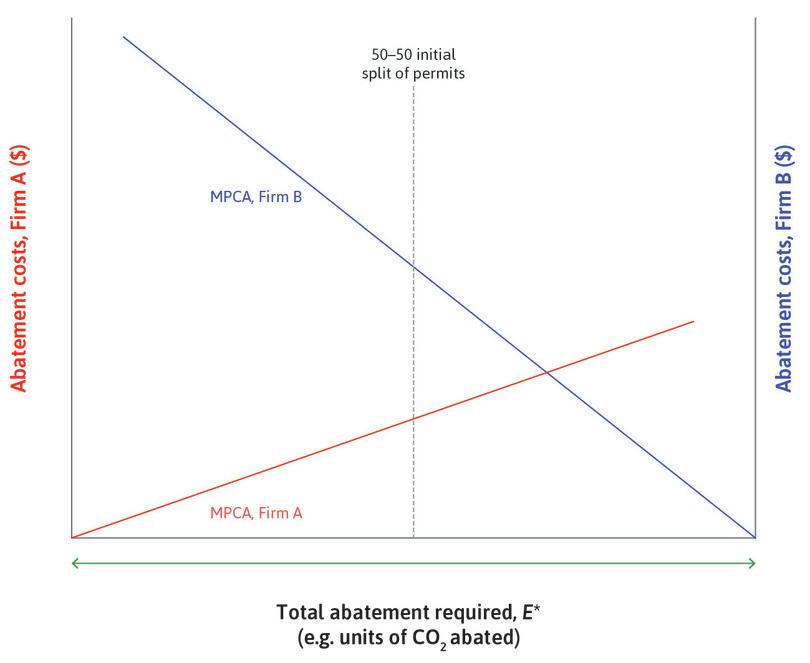

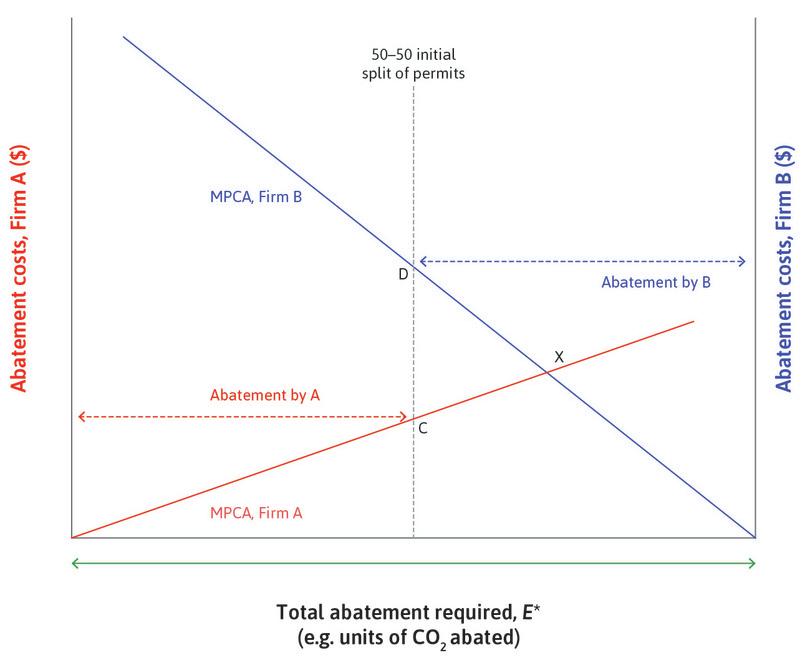

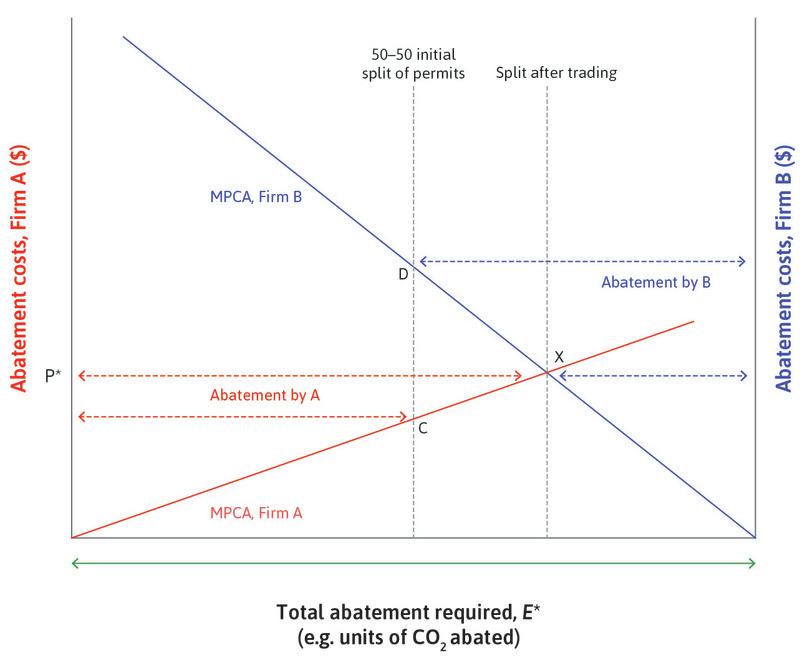

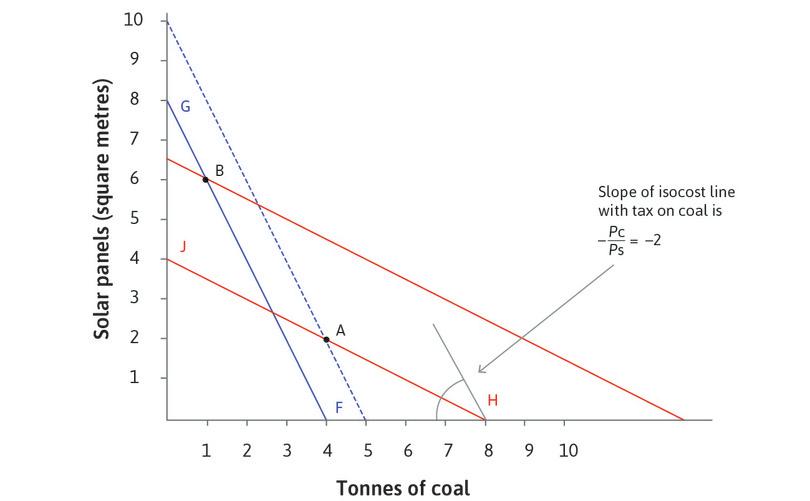

The desired level, however decided, is shown by the length of the horizontal axis in Figure 20.16. The question addressed by cap and trade is: given that firms vary in their production technologies, how will the total amount of required abatement be divided among them? The objective of a scheme for trading permits is that the abatement should be done by the firms for which this is least costly because this saves scarce resources that can be used elsewhere.

To see how this works, go through the analysis in Figure 20.16, which shows the case where the number of permits is initially divided equally between two firms with different costs of abatement.

There are many ways in which the permits might be traded once they are issued. One is the auction-type market studied in Unit 11, in which we saw (from an experiment) that the traders quickly converged to trading at a price like P*, which is the market-clearing price. The trading of permits achieves the desired level of abatement at the lowest resource cost to the economy. P* is the permit price and is equal to the marginal cost of abatement in the economy.

Cap and trade: Examples of emissions trading

One of the earliest cases of successful emissions trading was the sulphur dioxide (SO₂) cap and trade scheme in the US, implemented in the 1990s and intended to reduce acid rain. By 2007, annual SO₂ emissions had declined by 43% from 1990 levels, despite electricity generation from coal-fired power plants increasing more than 26% during the same period.

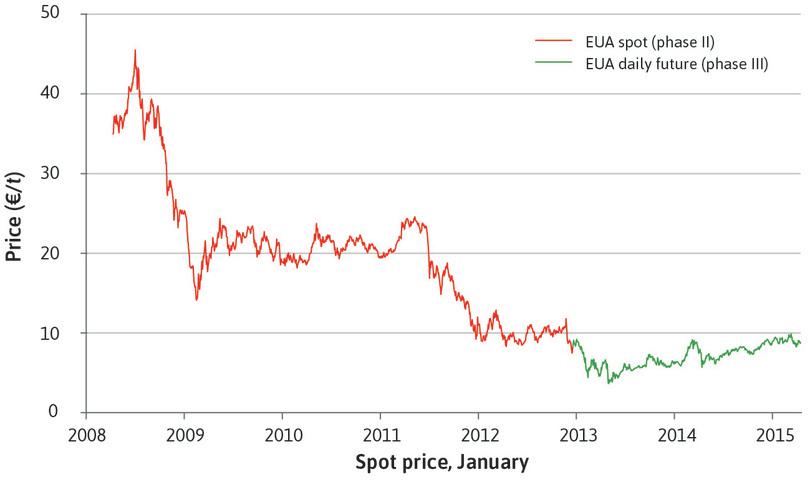

The European Union Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS), launched in 2005, is the largest CO₂ cap and trade scheme in the world, and now covers 11,000 polluting installations across the EU. National governments auction 57% of permits in the EU ETS, and the overall emission cap (that is, the amount E* in Figure 20.16) is tightened every year. Some of the auction proceeds are used to fund low-carbon energy innovation. Similar carbon trading schemes exist in other countries and regions.

The EU ETS has been less successful than the US SO₂ scheme. Some analysts think this is due largely to the fact that the permitted level of emissions was too high (too large a cap). After the financial crisis in Europe, lower aggregate demand caused the demand for electric power to shrink and with it, firms’ profit-maximizing emissions levels. With demand exceeding supply, the price of permits fell dramatically, providing little incentive for firms to undertake abatement expenditures. These effects are shown in Figure 20.17.

Permit prices in the European Union Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS).

Figure 20.17 Permit prices in the European Union Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS).

Data provided by SendeCO2 based on prices from Bloomberg Business.

This highlights a drawback of cap and trade. The price signal is not necessarily a reliable guide for future abatement investment decisions. In Germany, for example, the fall in permit prices led to several high-emitting coal power plants reopening, because dirty technology was profitable again.

But emissions trading schemes do not need to leave the market entirely free. The UK, for example, uses a carbon price floor, which sets a minimum price for British participants in the Emissions Trading Scheme. They do this to avoid the ‘virtually free pollution’ outcome that occurs when the permit price crashes.

The estimated total external cost of a tonne of carbon dioxide emissions differs depending on how we value future generations, as we shall see in Section 20.9. A low-end estimate in 2017 dollars is about $40 per tonne of CO₂ emissions, and it is rising fast because the greater the amount of CO₂ in the atmosphere, the higher the marginal effect on climate of adding more. The recent price of a permit on the European Union Emissions Trading Scheme (shown in Figure 20.17) is less than a fifth of this cost, so the permit plan is inducing decision-makers to internalize only a small fraction of the negative external effects.

Ideally, a tax on fossil fuels could entirely offset these external effects, with the added advantage that businesses and others would then face less uncertainty about the cost of burning carbon. A tax on carbon would raise the cost of emitting carbon in exactly the same way as having to pay for an emissions permit would do. In fact, the effect on costs would be identical if the market-determined cost of the permit were to be the same as the tax rate per tonne of emissions set by the government. The effect of the increase in costs would be higher prices of emissions-intensive goods and hence, ceteris paribus, demand for such goods would fall. Both the cap and trade and a carbon tax are said to be a way to ‘put a price on’ the external effects of carbon emissions.

How high should the price of carbon emissions be?

Given that producers and users of fossil fuels are usually heavily subsidized (at very different rates from country to country) the tax or the cost of a permit would have to exceed $40. On average around the world, fossil fuel subsidies are about $15 per tonne, so an optimal tax would be $55 per tonne (to internalize the external costs and to offset the subsidy). A simpler policy would be to eliminate the subsidies and set the carbon tax at our best estimate of the external cost of burning carbon.

The pros and cons of these two policies:

- a cap and trade permit based system with a sufficiently low cap

- a carbon tax at a sufficiently high rate to offset the external costs (and subsidies, if these remain)

These have been actively debated among environmental economists, with no clear consensus other than that either is preferable to the policies being pursued in most countries. Cap and trade, however, has been more popular, perhaps because it has the advantage of flexiblity. The ability to set the carbon price, but then to control the way in which permits are allocated and traded, gives the policymaker two ‘levers’. In contrast, a single tax may be politically unpopular for a policymaker to implement.

Exercise 20.5 Assessing cap and trade policies

- Explain why the green area in Figure 20.16 represents the total gains from trade. Hint: think about the first permit that Firm B buys from Firm A. How much is the most that Firm B would have been willing to pay? How much was the least that Firm A would have been willing to accept in order to part with the permit?

- How would you explain the way a cap and trade policy works to someone who has not studied economics? How would you respond to their concerns that the policy is likely to be ineffective or unfair? Many newspapers and blogs publish ‘op-eds’, that is, opinion editorials from the public. A common length limit is 600 words. Find some op-eds on climate policy, and having looked at how they are written, draft your answer to this question in the form of an op-ed.

Exercise 20.6 A successful tradable emissions permit program

The cap and trade sulphur dioxide permit program in the US successfully reduced emissions. The program costs were approximately one-fiftieth of the estimated benefits.

Read Robert Stavins and colleagues’ views on the US sulphur dioxide cap and trade program at VOXeu.org.

- In the view of the authors, why are cap and trade systems such powerful tools to achieve reductions in emissions?

Also read ‘The SO2 Allowance Trading System’ by Richard Schmalensee and Robert Stavins of the MIT Center for Energy and Environmental Policy Research.

- Summarize the evolution of permit prices using Figure 2 in the article.

- How well can the price movements in permit prices be explained by the analysis in Figure 20.16?

Look again at Hayek’s explanation of prices as messages (Unit 11), and the analyses of asset price bubbles (Unit 11) and housing bubbles (Unit 17).

- Could we use similar reasoning to explain price movements in Figure 2 of the paper by Schmalensee and Stavins?

Exercise 20.7 Would a carbon tax reduce emissions more than regulation?

In 2017, economists Martin Feldstein and Greg Mankiw (respectively economic advisors to US Presidents Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush), together with Ted Halstead, a climate campaigner, suggested in the op-ed ‘A Conservative Case for Climate Action’ that an ideal climate policy in the US should consist of three parts:

- A single carbon tax should replace all regulations that are aimed at reducing carbon emissions.

- Revenues collected from the tax should be refunded to American taxpayers in quarterly paychecks (‘carbon dividend’).

- American firms that export to countries without carbon taxes should not pay a carbon tax, while importers should face an import tax on the carbon contents of their products (a ‘carbon border adjustment’).

- Explain the economic reasoning behind each part of the proposal.

- Why do the economists think replacing regulations with a single carbon tax would be more efficient?

- Some environmental groups oppose the carbon dividend. They argue that the money could be better spent. Do you agree? What should carbon revenues be spent on? Do you think citizens are more likely to support a carbon tax if there is a carbon dividend?

- Why do the economists think a border carbon adjustment is necessary? What would be the effect of a domestic carbon tax without a border carbon adjustment? What incentives does it create for American companies and for foreign companies? Is it fair on firms from developing countries (who often generate a lot of electricity from high emissions coal) who export their products to the US?

- Do you support the proposal by Feldstein, Mankiw, and Halstead. Explain why or why not. What changes would you make?

20.6 The measurement challenges of environmental policy

To implement environmental policies using the framework we have provided, we need to measure the value of abatement.

Placing a value on the benefits of abatement is challenging because we are dealing with missing markets for environmental quality and uncertain long-term impacts. What is the value of preserving a rainforest, saving a threatened species, creating better air, or less noise? To answer these questions, different methods are used depending on whether the environmental issue in question is affecting environmental wellbeing, health, consumption, or future assets.

- hedonic pricing

- A method used to infer the economic value of unpriced environmental or perceptual qualities that affect the price of a marketed good. It allows a researcher to put a price on hard-to-quantify characteristics. Estimations are based on people’s revealed preferences, that is, the price they pay for one thing compared to another.

- contingent valuation

- A survey-based technique used to assess the value of non-market resources. Also known as: stated-preference model.

We examine two methods of measuring the benefits of abatement: hedonic pricing and contingent valuation.

Contingent valuation

Among the easiest and most widely used methods of valuing the benefits of abatement is simply to ask people. For example, after the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill in Alaska, which released 11 million gallons (42 million litres) of crude oil into beautiful Prince William Sound, the court used contingent valuation to assess the value of the losses (such as the value of natural beauty) caused by the spill. They did this in a survey by asking respondents how much they would be willing to pay to prevent a new spill. The study estimated the lost value in 1990 to be at least $2.8 billion. Exxon eventually paid $1 billion in damages in a settlement with the governments of Alaska and the US.

Researchers used contingent valuation techniques to get a quantitative estimate of the value of elephant conservation in Sri Lanka. Farmers were killing elephants to protect crops and homes. The researchers wanted to know how much Sri Lankans would be willing to pay to the farmers as compensation for the damages caused by the elephants, if the farmers stopped killing them.2

Contingent evaluation is called a stated preference approach because it is survey-based and accepts the respondents’ statements of their values as indicative of their true preferences. This is not the case for hedonic pricing.

Hedonic pricing

Hedonic pricing is called a revealed preference approach because it uses people’s economic behaviour (not their statements) to reveal what their preferences are. Laboratory experiments are a similar method of studying revealed preferences, as we saw in Unit 4. But lab experiments are not very useful in valuing the environment.

For example, how much do you value having your residence being free of the sound of aircraft flying overhead? Economists observe that houses under aircraft flight paths are sold for less than equivalent houses in quieter locations. By comparing data on house prices, we can calculate the amount people are prepared to pay to avoid the noise pollution.

This technique was used in the UK to set the tax for landfill waste. The marginal benefits of abatement were estimated in a study that used data on more than half a million housing transactions over the period 1991–2000. By controlling for a large number of factors that can account for the variation in house prices, the researchers then tested whether any of the variation left unexplained could be accounted for by the proximity of the house to a landfill site. The researchers found that being within a quarter of a mile (400 metres) of a working landfill site reduced house prices by 7%. They calculated that the marginal benefit from reducing the proximity to a landfill site was £2.86 per tonne of waste (in 2003 prices).

Hedonic pricing and contingent valuation give us a way to measure the way people value a particular change in the environment given their experience of this change. Green growth accounting gives us a way to estimate the value of conserving environmental resources for society as a whole, today and in the future. Below, you will learn about how some economists are placing a monetary value on society’s use of natural assets.

How economists learn from facts Natural capital and green growth

- depreciation

- The loss in value of a form of wealth that occurs either through use (wear and tear) or the passage of time (obsolescence).

Recall that depreciation refers to the wearing out or using up of the physical capital goods used in production. In the green growth accounting framework, the environment is similarly considered as an asset that can be used up. The environment is part of what society needs to produce goods and services. Thus, environmental degradation reduces the assets of the society in much the same way as the wear and tear or obsolescence of machines used in production.

Remember that income is the most a person, or a nation, could consume without reducing its capacity to produce in the future. This was the message of the bathtub in Unit 10. Income is the flow of water into the tub minus the amount of evaporation that is reducing the total amount of water in the tub. Income according to this definition is gross income minus depreciation.

Although environmental degradation is not measured in conventional national accounts, it should be, because using up our natural capital is no different from the wear and tear on the machines and other equipment we use.

The World Bank estimates that in low-income countries, natural capital comprises 36% of wealth, so using some of this up and not counting the loss overstates how fast income is really growing. By how much though? In order to take natural capital loss into account, we must figure out how much it will cost (per year) to replace the lost natural capital and then subtract it from the annual GDP figure (remember that the most common measure of income, GDP, does not even take account of the depreciation of capital goods because of difficulties with measurement).

- green adjustment

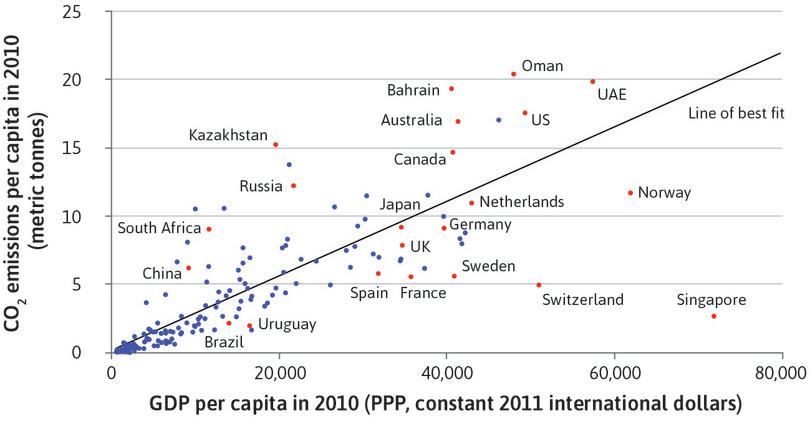

- Accounting adjustment made to conventional measures of national income to include the value of natural capital.